Mutant variants, emerging overseas or domestically, are an inevitable biological reality once a virus is in the population.

On 9 February 2021, Health Secretary Matt Hancock announced that travellers from ‘hotspot countries’ will be expected to pay £1,750 to stay in one of 16 hotels signed up for mandatory quarantine. A maximum 10-year jail term for lying about recent travel history has been defended by the Government. It follows concerns that existing vaccines being rolled out in the UK may struggle to control ‘new virus variants’ identified around the world.1 These fears are not supported by any robust scientific evidence.

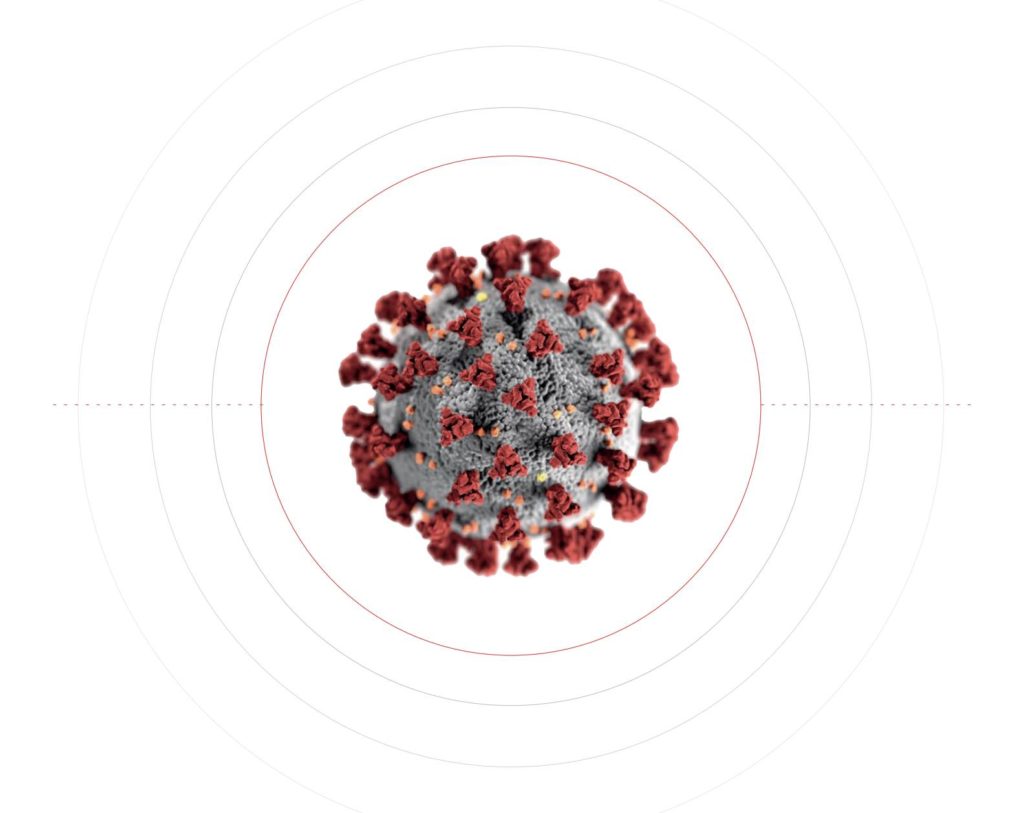

SARS-CoV-2 is a large virus (approx 30,000 RNA bases, 10,000 amino acids2). Currently the greatest difference between any ‘mutant variant’ and the original Wuhan sequence is limited to only 17 point mutations.3 The genomic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 in circulation in different continents is fairly uniform.4

We know that the mutation rate in SARS-CoV-2 is slower than other RNA viruses because it benefits from a proofreading enzyme which limits potentially lethal copying errors.5 These mutations have caused changes in less than 0.2% of the entire virus sequence. All variants are therefore currently 99.8% similar to the original Wuhan viral sequence. Our immune system recognises many different parts of the virus including membrane proteins, capsules, small envelope proteins and the spike protein. It is the overall shapes of these viral proteins (epitopes) that are recognised by our immune system. The spike protein tends to receive more attention purely because it attaches to the ACE receptors that allow entry into cells.

Natural immunity to SARS-CoV-2 is acquired by the immune system ‘cutting up’ the virus into hundreds of pieces.6 Many of these pieces are then used to develop a suitably diverse immune response to the virus. Specialised immune cells will launch an immune response if exposed to the same ‘learned’ viral fragments in the future. Prior immunity gained from the original SARS-CoV-2 should work perfectly well against any new ‘mutant variant’, given high levels of sequence similarity. It is important to also note that in the highly unlikely event that a variant did manage to escape a person’s acquired immune response, this would represent a threat to an individual rather than a community.

There has, to date been no robust scientific evidence provided that any variant so far identified is more transmissible or deadly than the original.7 By definition, variants are clinically identical. Once there is a clinical difference then a new “strain” of virus has emerged. Prior knowledge of viral mutation shows they usually evolve to become less deadly and more transmissible.8,9 This optimises their chance of spreading as dead hosts tend not to spread virus and very ill hosts reduce their contact with others.10 There is also the possibility that lockdowns have somehow interrupted ‘competitive’ viral natural selection. However, this is a separate issue and border closures will not prevent such a phenomenon in any case.11

Sir Patrick Vallance said at the press conference on 10 February 2021: “We are seeing the same variants popping up all over the world and that is what you would expect.”12 It is worth noting that many of these new variants emerged in countries that had already conducted vaccine trials, i.e. South Africa, Brazil and the UK. Given the reported clusters of sudden outbreaks of COVID-19 in care home residents and staff in the days following the vaccination programme, this observation justifies immediate investigation.13

Naturally acquired cross-immunity almost certainly applies to vaccine-acquired immunity, although to a lesser extent. This is because the mRNA vaccines mimic the spike protein, instead of a combination of several parts of the original SARS-CoV-2.14 It should be noted that the spike protein has over 1,200 amino acids.15 It is highly unlikely that a variant with minor changes in the sequence will evade the acquired immune response.

Closing international borders to keep out ‘foreign mutants’ of an already endemic virus is neither useful nor possible. Mutant variants from abroad pose no extra threat to the citizens compared with homegrown variants and may even have very similar sequences. In addition, once a virus is established in a population, as is the case in the UK, it will mutate slowly over time, irrespective of borders. That particular horse has already bolted and is a biological reality we must all learn to live with.

There are however some positive points to be drawn from the available evidence. The virus will eventually run out of viable hosts due to rising population immunity. In addition, many different studies have shown that infection with one of the other seasonal human coronaviruses (shCoVs) responsible for the common cold confers a cross-reactive T-cell immune response to SARS-CoV-2. At least six studies have reported T-cell reactivity against SARS-CoV-2 in between 20% to 50% of people with no known exposure to the virus.16 An education drive explaining the concept of pre-existing immunity could be extremely helpful to alleviate fear in the general public.

It is a fallacy to assume that because the genome of a virus has been sequenced for the first time in a particular country, it must have originated in that country. Correlation does not equal causation. On the contrary, successful mutations with regard to natural selection will crop up anywhere. It is sometimes referred to as convergent evolution. This is one reason the so-called ‘UK variant’ has already been found in over 46 countries. International borders have nothing to do with the emergence of viral mutations. To convey this idea to the public, given the enormous economic implications of shutting international borders, would be a costly mistake.

Endnotes

1. COVID-19: 10-year jail term for travel lies defended

2. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by the numbers

3. Genetic diversity and evolution of SARS-CoV-2

4. No evidence for increased transmissibility from recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2

5. No evidence for increased transmissibility from recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2

6. Immune responses to viruses

7. No evidence for increased transmissibility from recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2

8. We shouldn’t worry when a virus mutates during disease outbreaks

9. Negligible impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants on CD4 + and CD8 + T cell reactivity in COVID-10 exposed donors and vaccinees

10. The Evolution and Emergence of RNA Viruses

11. Stresses and strains: the evolution of Covid is not random

12. Coronavirus press conference (10 February 2021)

13. UKMFA : Urgent warning re COVID-19 vaccine-related deaths in the elderly and Care Homes

14. Understanding mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines

15. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein : potential anti-virus drug development for COVID-19

16. COVID-19: Do many people have pre-existing immunity?