Mortality risk from COVID-19

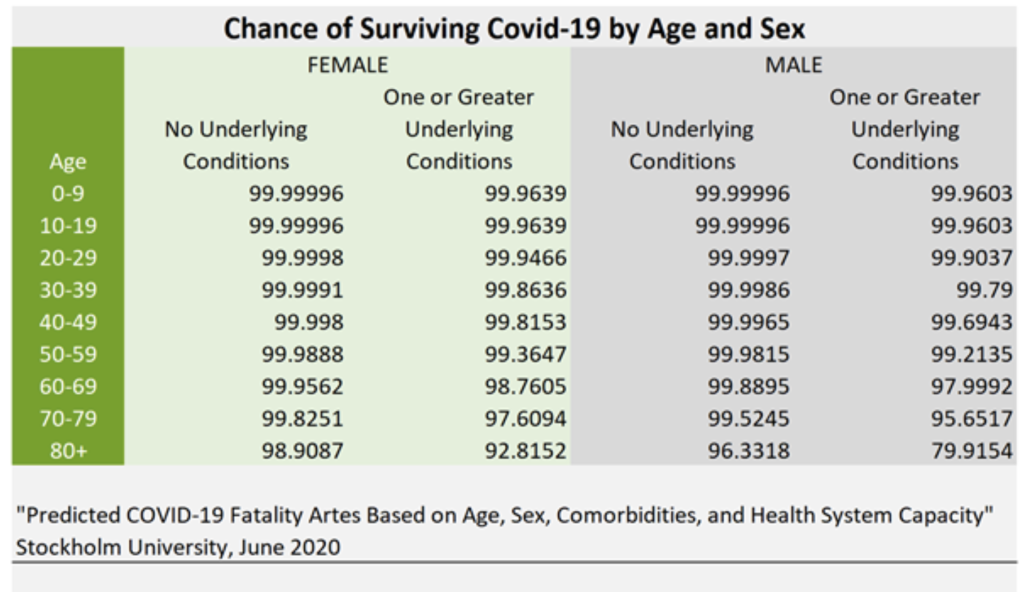

The constant portrayal of COVID-19 as a threat has caused distortion in people’s perception of their risk of dying from it, if they are unlucky enough to catch it. The risks of dying are dependent on age and comorbidities, e.g.:

| Healthy 35-year-old woman | If unlucky enough to catch coronavirus, chance of surviving = 99.9991% The chance of dying is less than the fatality risk of a general anaesthetic for a procedure |

| 55-year-old man with co-morbidities* | If unlucky enough to catch coronavirus, chance of surviving = 99.2135% The chance of dying is less than the risk of an average 55-64 year old dying of any cause this year |

| Healthy 75-year-old woman | If unlucky enough to catch coronavirus, chance of surviving = 99.8251% The chance of dying is less than the risk of being injured in a car accident each year |

| 85 year old man with co-morbidities* | If unlucky enough to catch coronavirus, chance of surviving = 79.9154% The chance of dying is less than the risk of living for one year in a care home |

*comorbidities included in the study were: cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, chronic liver disease, diabetes mellitus, cancers with direct immunosuppression, cancers with possible immunosuppression, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, chronic neurological disorders, sickle cell disorders.

This data will be an overestimate as it comes from table 1 of this study published in August 2020. The study estimated an overall infection fatality rate in Western Europe to be over 1% and even Professor Neil Ferguson agrees that it is more like 0.8% with WHO estimates now substantially lower than that.

You can calculate your own risk of a fatal infection using the Oxford University QCovid calculator, although it is worth bearing in mind that these figures were based on the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in the spring 2020 peak, and test positivity rates in England are now just 4% of that level. Therefore results from this calculator are likely to be higher than the actual current risk.

No-one can die of COVID-19 without catching the virus. The chances of catching it currently are minimal as there are so few genuine cases (in other words, people with symptoms, usually severe). Even after testing millions of school children and surge testing in certain London boroughs the test positivity remains stubbornly low.

Deaths are now at levels last seen in July. Due to the lag time between infection and death, reported figures on mortality do not indicate current infection rates but rather reflect the situation at least three weeks prior to this. The exceptionally low daily deaths we are now experiencing reflect the lack of emergency. Despite this, only 15 people are currently allowed to attend a wake and the Queen had to sit alone during her husband’s funeral service, whilst professional football players can celebrate goals with displays of enthusiastic hugging and embracing.

There is no evidence that any variant is more deadly. Papers, that have been picked up by the press and that suggest otherwise have not accounted for underlying morbidities which we know have a significant impact on deaths.

New guidance for Covid vaccination in pregnancy

On 16 April PHE issued new guidance on COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant women so as to include the advice that pregnant women: “should be offered Covid-19 vaccine at the same time as the rest of the population, based on their age and clinical risk group”.

This seems totally contrary to established precautionary principle, given that:

- Pregnant women were not included in any of the trials, and animal trials conducted have been extremely limited. Real world studies have insufficient data. We therefore cannot be sure they are safe.

- The current clinical trials do not complete until end-2022 earliest, the current vaccines are not approved products and are being administered under emergency waivers.

- The trial data available to date indicate extremely modest reductions in absolute risk on an individual basis (<1%) in the populations studied.

- The infection fatality rate for women of child-bearing age is <0.05% with no convincing evidence of any greater risk in pregnancy, although there is some increased risk of preterm birth for symptomatic women.

- There are a number of signals which could be of concern to fetal health emerging from real-world use – not limited to the AstraZeneca vaccine or any age groups or other known risk factors – prompting guidance from the British Society of Haematologists.

Following the thalidomide tragedy in the 1960s, important changes were made to the way drugs were tested and approved across the world. The Yellow Card Scheme was set up so side effects from medications could be tracked and crucially, trials for substances marketed to pregnant women had to provide evidence that they were safe for use during pregnancy. Before March 2020, when COVID-19 became the government’s sole health focus, it was understood that medication should only be used during pregnancy if absolutely essential.

“Why are so many babies dying of Covid-19 in Brazil?”

This alarming headline appeared in BBC Global News, regarding a child who died from COVID-19 complications in Brazil. It has had considerable coverage but, as with all deaths, it needs to be seen in context. Brazil is a vast country with a population of 230 million and 375,000 COVID-19 deaths to date. The article states that 1,300 babies have died of COVID-19 which therefore represents 0.34% of COVID-19 deaths. In the UK and six other countries following child deaths throughout the pandemic, the UK had 7 deaths in children under 10 years, all of whom had severe life-limiting conditions, which accounts for 0.19% of all cause deaths for this age group. Also the background infant mortality rate in Brazil at 17.5/1000 is four times higher than that of the UK.

The BBC report focuses on a tragic account highlighting the problems for access to appropriate hospital care, in low and middle income countries. Even when the toddler was obviously getting sicker, the parents were too afraid to take him to hospital, a problem echoed in the UK. By the time they did so, he required immediate intensive care, necessitating a long transfer journey to the regional centre where appropriate treatment could be given. It is clear that the vast majority of children who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 have no or very mild symptoms. For those children in the UK who do develop the rare post-covid inflammatory multiorgan syndrome (PIMS), a complete recovery has been the norm. The RCPCH has a very useful information pack for parents.

No evidence of widespread symptomatic reinfection

The Telegraph’s Global Health team live blog recently featured the headline, at 2.47pm, that Previous coronavirus infection does not fully protect young people against reinfection, research suggests.

The article says “Researchers said that despite previous infection and the presence of antibodies, vaccination is still necessary to boost immune responses, prevent reinfection and reduce transmission.”. The paper itself was not cited by The Telegraph, although it must surely be this one published in The Lancet.

HART experts are not aware of credible evidence of widespread symptomatic reinfection, in other words reinfection leading to illness. And indeed, the study in question equates infection with PCR results rather than actual illness.

Natural immunity generates a much broader range of immunity than the currently formulated spike protein vaccines, particularly for young, fit people, to whom the researchers believe the risk applies. They are urged to “take up the vaccine whenever possible” – despite the fact that natural immunity is effective and long-lasting against illness for respiratory viruses such as SARS-CoV-2.

It is also an assertion that is not backed up by the study which did not test what the level of reinfection would look like in a vaccinated population. The study states that ‘it is possible that both previously infected and vaccinated individuals might later become infected’- which surely is not an argument for vaccinating healthy young people, who are at a vanishingly small risk of suffering serious illness.

Media coverage of variants

The use of variants to perpetuate the fear narrative is misleading and becoming an unhealthy obsession. First cited months ago to cancel Christmas, variants are now being used as the primary reason to keep borders closed and to make the case for vaccine boosters.

To date, the mainstream reporting of variants is littered with words like ‘might’, ‘could be’, ‘possibly’ when talking about how deadly and transmissible they may or may not be. These ‘maybe’ ideas never seem to evolve into actual scientific proof. In a world of social distancing, we may in fact be distorting the competitive advantage of the more transmissible/less virulent variants, preventing the virus from evolving into a more benign form. Meanwhile, these interventions are destroying livelihoods, demolishing our culture, threatening our democracy and, by the government’s own admission, putting thousands of lives in danger.

Variants are normal and unavoidable. A study published in June analysed 48,000 samples and found 350,000 different mutations. They are not extraordinary, nor are they necessarily cause for alarm. The only reason we know about these in this particular virus is due to the ongoing and pervasive focus on them. Had we scrutinised any other previous respiratory virus in the same way, we would no doubt have found similar. The fact also remains that if a variant becomes too different via mutations, usually it can no longer function as a virus.

The emotive idea of ‘mutant variants’ has been used to enforce more and more control on the lives of UK citizens. What is puzzling, is the lack of immunology or virology expertise called upon when discussing the topic in the media. Rather, they refer to experts from other unrelated fields. The misinformation that ensues, and becomes embedded in the minds of the general public, seems like media bias to increase fear. There is a desperate need for journalists to present accurately researched information on this topic, from highly qualified individuals within relevant fields.