Canada is killing with kindness

It is easy to make an argument for euthanasia. Heart wrenching stories can be told about people who are suffering terribly and genuinely want to see their already imminent death hastened. The argument for not crossing this line is because as soon as it is crossed there is a very slippery slope on the other side. Canada has demonstrated this in a most tragic way.

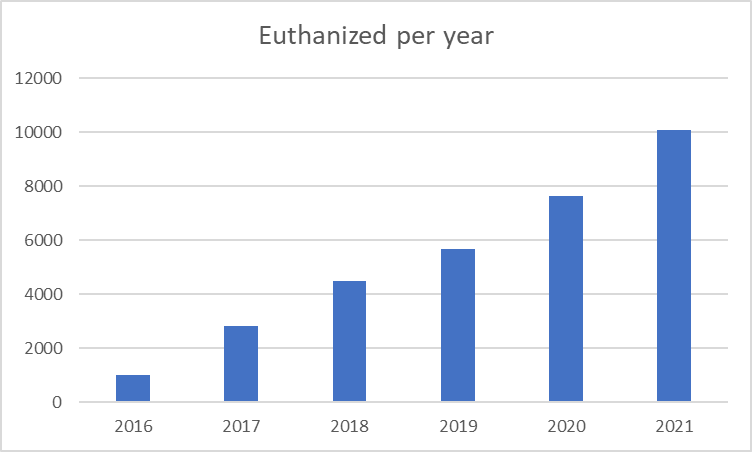

Canada legalised euthanasia six years ago through the Medical Assistance in Dying bill (MAiD). Since its inception, over thirty thousand Canadians have been euthanized. The number has increased by about a third each year. By 2021 states sponsored homicide accounted for over 3% of all deaths. For comparison diabetes accounts for 2.5% and influenza and pneumonia together accounted for less than 2% in 2020.

Figure 1: Number of state sponsored deaths per year

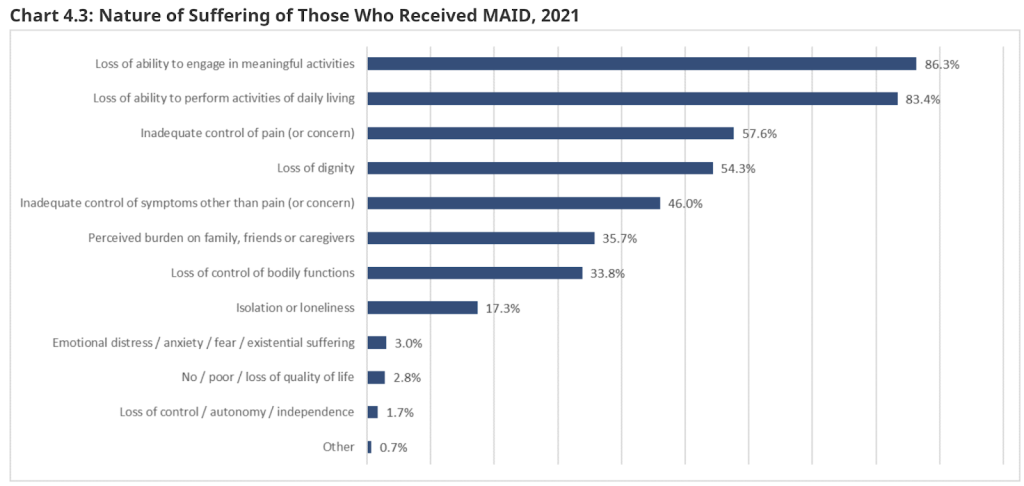

Figure 2: Reasons given for undergoing euthanasia in Canada.

The line in the sand that you do not kill has been utterly trampled over in Canada. Even the religious have lost their moral compass over this. One woman was killed by doctors in her church while religious leaders prayed over her. The church leaders claimed no-one expressed concern about this happening in a church.

Having crossed the line of “do not kill” there seems to have been little thought about drawing a new line in the sand that must not be crossed. There seems to have been little consideration of who and how many should be involved in the decision making. Note that more than a third of those killed felt they were a burden and one in six felt isolated or lonely (figure 2).

One of the most alarming developments from the implementation of MAiD is the case of a Canadian man who was approved for euthanasia due to his dire financial condition. This case underlines a chilling progression from euthanasia as an option for those in unbearable physical pain to a choice for individuals facing socioeconomic challenges. A survey showed that 28% of Canadians support euthanasia for homelessness and 27% for poverty. One family reported to the authorities the death of their depressed loved one in a hospital, where he was killed despite concerns being raised by the family and by nursing staff that he lacked capacity.

The notion of the ‘slippery slope’ is rooted in psychological research, particularly in relation to moral decision-making. An example is an experiment published in the Journal of Applied Psychology. It was found that participants were more likely to cheat when the reward started at a small amount and gradually increased. This gradual acceptance of unethical behaviour over time underscores the crux of the slippery slope effect.

By allowing euthanasia for individuals suffering physical pain, Canada may have unknowingly trampled on the path of ethical ambiguity, leading to euthanasia being used as a solution for conditions like poverty. This parallels the gradual acceptance of laws, cultural trends, and political misconduct that were initially unthinkable.

Drawing parallels with the regulation of public health, a similar ‘slippery slope’ scenario can be observed. While the intention behind banning smoking in public spaces was laudable, this move empowered public health bodies to impose further restrictions, gradually leading to what some critics label a ‘public health totalitarian state.’

To counter the ‘slippery slope’, researchers recommend a ‘prevention focus’, a psychological strategy emphasising vigilance and security. This approach involves considering the potential losses and negative outcomes of decisions before implementing them. Had this approach been more central to the discussion around MAiD, Canada might have avoided some of the ethically contentious situations it now faces.

Euthanasia is now legal in Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand and Spain and parts of Australia. It is important that we start a public debate now. It is all the more important given that over the last few years it has become clear that we are living in a society with no respect for bodily autonomy. How long before it is accepted that “being a burden” is a just reason for killing. How much longer before people without capacity are considered to be too much of a burden?

The Canadian example underlines the dangers of the slippery slope in legalising euthanasia. The country’s experience shows that while euthanasia may be intended for individuals in unbearable physical pain, its application can gradually expand to cover other conditions, blurring ethical boundaries. It serves as a cautionary tale for other countries debating euthanasia legislation, urging them to consider potential ‘slippery slope’ implications before taking a decision.