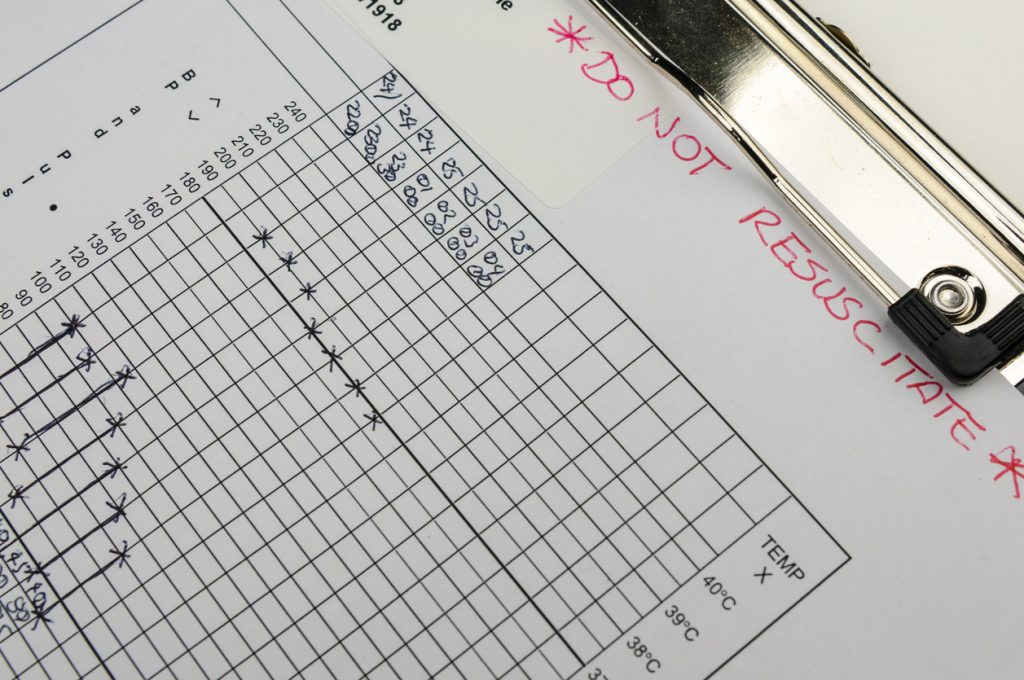

Care withheld without consent

In spring 2020, certain groups were denied access to care based on their age, frailty, and underlying health conditions. Blanket Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders were issued, without the patient’s consent. Certain hospitals also introduced a policy of not admitting anyone who had a DNR such that active medical care was also denied. How did this come about?

The decisions made to ration care were not universal, but they were applied to whole groups, such as entire care homes or those with learning difficulties on a specific GP’s list, without individual consideration. The fear of pressure on intensive care units created an environment where such decisions may have felt justified. If resuscitation is successful, the patient often then requires intensive care. Any new limitations on access to intensive care means a change to decisions on resuscitation might be considered, in good faith, by doctors.

The investigative team of the Sunday Times, Insight, carried out an investigation into deaths in the elderly during spring 2020. In it they reported that Mark Griffiths, a Professor of critical care medicine at Imperial College London created a document “Covid-19 triage score: sum of 3 domain.” It suggested patients would be scored based on age, frailty and underlying conditions. Anyone over the age of 80 would score too high to be treated and anyone aged over 75 years with frailty score added in would too. Even people over the age of 60 would be denied care if they were frail and had underlying health conditions. After discussion the document was rewritten with adjustments to the scoring, given an NHS logo and presented to ministers on March 28th 2020. The intention was that such triage should be used only when capacity was at risk of being breached, but the chair of the group who wrote the original document said it had been distributed to doctors and hospitals as part of the consultation process, and “we were aware that some of them were looking at that tool…Some of them were using it.” A version of the document was uploaded onto NHS Highland’s internal internet.

In March 2020, NICE issued guidance on do not resuscitate orders. The Chief Executive of MenCap said:

“latest NICE guidance for NHS intensive care doctors could result in patients with a learning disability not getting equal access to critical care and potentially dying avoidably. These guidelines suggest that those who can’t do everyday tasks like cooking, managing money and personal care independently – all things that people with a learning disability often need support with – might not get intensive care treatment.”

Subsequently, NICE guidance had to be amended on 25th March 2020. NHS England followed up with letters on 3rd and 7th April to clarify that treatment decisions should not be made based on the presence of learning disabilities or autism alone and emphasised the importance of individualised care.

The BMA issued guidance on 3rd April 2020, stating that a simple ‘cut-off’ policy based on age or disability would be unlawful as it would constitute direct discrimination. They acknowledged that older patients with severe respiratory failure secondary to covid may have a lower priority for admission to intensive care due to their high chance of dying despite treatment. They argued that a ‘capacity to benefit quickly’ test would be lawful in the circumstances of a serious pandemic.

Reports of people with learning difficulties being given DNR orders emerged. The Somerset Parent Carer Forum wrote a letter saying:

“We have been made aware of concerning media reports nationally and locally regard [sic] the use of Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR) forms. These reports have centred around particular GP’s deeming that some adults with learning disabilities should not be DNR… We have reported our concerns to Somerset Clinical Commissioning group that this has happened with [sic] our area and they are taking this matter very seriously. The Clinical Commissioning Group are investigating the report that have been made and have assured us that [sic] will take appropriate action.”

The triage tools were criticised by intensive care physicians saying:

“Implementation of such tools could prevent healthy, independent individuals from having an opportunity to benefit from AICU [adult intensive care unit] review/admission by protocolised counting of variables that do not predict whether they would personally benefit from AICU care.”

90% of those who died of covid before 4th April 2020 had not had access to intensive care and those that did were far healthier than the usual cohort of patients admitted to intensive care with viral pneumonias. Intensive care consultant Ron Daniels explained on BBC news how the new triage system meant that patients with a lower chance of survival were not receiving the care they would have normally.

Matt Hancock, Secretary of State for Health, felt the need to make it clear on 30th April that blanket DNR orders were unacceptable and that these decisions should always be personalised:

“And we’re making crystal-clear that it is unacceptable for advanced care plans, including ‘do not attempt to resuscitate’ orders, to be applied in a blanket fashion to any group of people. This must always be a personalised process, as it always has been.”

The Care Quality Commission carried out a review of the issue “of unacceptable and inappropriate DNACPRs [do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation] being made at the start of the pandemic.”

A survey of care home staff revealed that 16 respondents reported blanket DNR orders, which led to hospital admission being refused. The report by The Queen’s Nursing Institute said there were “blanket DNACPR instructions from the GP or the CCG or hospitals putting DNACPR in place without discussion with the resident, family or care home. Also, hospitals refusing to admit patients who had DNACPR or blanket ‘no admission’ policy.”

The report quoted respondents who challenged these blanket policies on the basis that they were unethical; these respondents also criticised their implementation without proper consultation or consideration for the patient’s quality of life:

“We were advised to have them in place for all residents. We acted in accordance with medical advice and resident wishes, not as advised by a directive to put in place for all by a CCG representative. We challenged this as unethical.”

”Sometimes changed without inclusion of family or the resident (where appropriate). Not always made including quality of life rather than disease and age.”

“Put in place without family consent by Trust staff, no consultation with staff in home.”

On 9th April, an extraordinary document was distributed by the Buckinghamshire NHS Trust, urging clinicians and GPs to “identify all patients who are frail or in the latter stages of life and score them based on their level of frailty”. The document stated that this approach was being adopted by clinical commissioning groups across England, with the intention of creating a list of those who would stay at home when seriously ill, rather than being taken to hospital.

NHS England issued advice on 10th April to health authorities, outlining broad groups of elderly people who should not ordinarily be conveyed to hospital unless authorised by a senior colleague. This list included all care home residents and patients who had asked not to receive an intravenous drip or to be resuscitated, effectively suggesting that those who had accepted DNR orders might be denied general hospital care.

Ambulance triage guidance was also changed on 10th April, as a higher triage score than normal was being used prior to that date. In the words of one paramedic, patients who needed care “were just being left at home.”

NICE issued guidance in April 2020, stating

“Be aware that older people, or those with comorbidities, frailty, impaired immunity or a reduced ability to cough and clear secretions, are more likely to develop severe pneumonia. Because this can lead to respiratory failure and death, hospital admission would have been the usual recommendation for these people before the COVID 19 pandemic. When making decisions about hospital admission, take into account:

-the severity of the pneumonia, including symptoms and signs of more severe illness

-the benefits, risks and disadvantages of hospital admission

-the care that can be offered in hospital compared with at home

-the patient’s wishes and care plans

-service delivery issues and local NHS resources during the COVID‑19 pandemic.”

It is crucial that we recognize and address the shortcomings in our healthcare system. It is through honest and open discussions about these issues that we can learn from our mistakes and improve our healthcare system for the future. The passion and anger in revealing these truths should not be silenced but rather embraced as a catalyst for change.