Parallels for today

Dr Ali Haggett

I was late to the party watching the mini-series ‘Dopesick’. When it was first released in October 2021 on the streaming service Hulu, I avoided watching it – in part because I was already familiar with the story and the script, but also because watching the corruption of science and medicine over the last four years has been challenging to witness. Indulging in more of it on the screen seemed counterproductive to wellbeing.

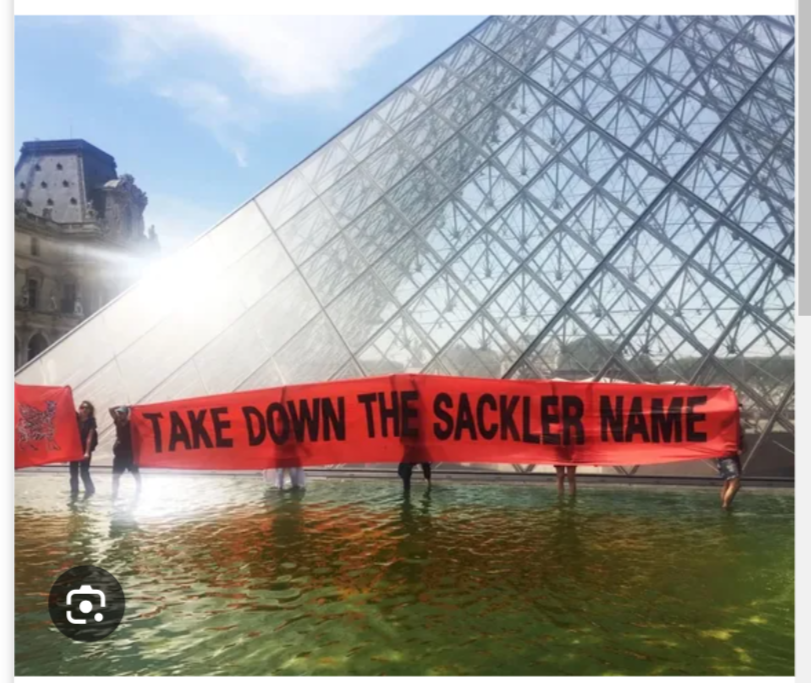

‘Dopesick’ charts the harrowing scandal of OxyContin addiction in the USA, from its origins in Appalachia, one of the first areas identified by the Sackler family of Purdue Pharma to target their new opioid pain relief medication. The Sacklers claimed OxyContin was non-addictive, and aggressively marketed the drug for relief from moderate pain, instead of severe pain (which required vigilant supervision by a clinician). These claims, couched in the humanitarian discourse of ‘changing attitudes towards pain management’, led to a drastic increase in opioid addiction and drug overdose deaths across the USA. The tragedy was amplified by the complete failure of the FDA to act on evidence about the dangers of OxyContin, and the mini-series brutally demonstrates the wanton medical and ethical disregard of patient safety, as Purdue Pharma blamed the ‘abusers’, diverting accountability away from pharmaceutical companies and regulatory bodies. The Sacklers still refuse to admit any personal liability for the opioid crisis, leading to the unenviable reputation of being labelled the most evil family in America.

This playbook is not new to me. As a medical historian who has published two books on gender, depression, neurosis and pharmaceutical prescribing in the 1960s and 1970s, I documented how dishonest and aggressive marketing was evident with the first major tranquiliser, chlorpromazine. This was promoted under the trade name Largactil, which literally meant ‘large-acting’, and it was advertised as ‘highly versatile’ – suitable for widespread use in general medicine, psychiatry, geriatrics, anaesthesia, neurology, obstetrics and even paediatrics. The new psychopharmaceuticals of the 1960s were not appropriate for treating those with mild or moderate symptoms, but pharmaceutical companies recognised that increasing numbers of people were seeking medical advice for ‘neurotic’ disorders and began research into this new and lucrative market. In the USA, meprobamate (marketed as Miltown) became the most popular drug prescribed in primary care – in the UK, prescriptions for the same drug (marketed as ‘Equanil’) rose sharply in the early 1960s. Increasing competition in the market for psychological disturbance, resulted in manufacturers constructing specific profiles for new groups of drugs such as the tricyclics and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors. F. Hoffmann-La Roche perfected this technique with their powerful group of benzodiazepine drugs. Exploiting the bad reputation of the earlier barbiturate sedatives, they suggested that the first of the benzodiazepines, marketed in 1960 as Librium, was at the cutting edge of psychopharmaceutical treatments for neurosis and anxiety. Valium emerged in 1963, more potent than its predecessor, and marketed for ‘psychic tension’ which set it apart from Librium’s less powerful indication for anxiety.

Increasingly prescribed for a myriad of social problems, concerns about tolerance, dependence and withdrawal soon emerged. The Rolling Stones’ song, Mother’s Little Helper, released in 1966, reflected disquiet about the potential hazards of addiction and overdose. By the early 1970s, some clinicians raised concerns about dependence, even at recommended doses. However, the scientific literature focused primarily on reports of addiction where patients had escalated their own doses. An absence of high-quality epidemiological surveys prompted the UK regulatory agencies to dismiss the idea that patients could become dependent at normal doses. The notion of an ‘addictive personality’ was mooted, diverting responsibility towards the character of the patient, and away from pharmaceutical companies and clinicians. By the early 1990s, experts in psychopharmacology estimated that approximately 500,000 people had become dependent on benzodiazepines in the UK, with double that number in the USA. For those people, if withdrawal was possible at all, it caused ‘great symptomatic distress’.

More recently, in the USA, Johnson & Johnson was fined $572 million in 2019 for fuelling Oklahoma’s opioid addiction crisis. Oklahoma’s Attorney General claimed the company used misleading information to downplay the risks of opioids and repeatedly ignored warnings by the Federal Government and its own scientific advisors about the dangers of its drugs. In 2004, the drug company Merck withdrew its blockbuster arthritis drug Vioxx, because it doubled the risk of heart attacks and strokes. Most disturbingly, a UK report by the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review, ‘First Do No Harm’, described serious harm from three other medical products: Primodos – a hormone-based pregnancy test used in the 1960s and 1970s, which caused miscarriages and birth defects; sodium valproate – an epilepsy treatment that caused birth defects and developmental delay in unborn children; and the pelvic mesh implant for organ prolapse in women, which has been found to cause internal damage, sepsis and chronic pain. The report found that patients’ voices were ignored, and that action was taken too late.

Fast forward to 2020 and, in a time of crisis, it was to these pharmaceutical companies that we turned with our response to covid. We might not have been dealing with opioids and addiction; however, we saw the same playbook orchestrated from big pharma and government regulatory agencies. The MHRA is in part funded by the Pharmaceutical Industry and by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which also fund drug trials and prestigious medical journals, acting as gate-keepers over raw data. Twenty years ago, the then Editor of the Lancet declared that: ‘Journals have devolved into information laundering operations for the pharmaceutical industry’. Widespread concern remains about conflicts of interest among government advisors and their seamless career paths, which propel advisors back and forth to senior executive positions or consulting roles with pharmaceutical companies.

In medicine and science, university departments have become instruments of industry – and even in the humanities (history of medicine, which is my field), the success or failure of funding applications will be determined by bodies such as the Wellcome Trust with broader scientific and political agendas. As with the Oxycontin and benzodiazepine scandals, our regulatory bodies and our government have failed almost entirely to acknowledge mistakes and dangers. Recent House of Commons debates about excess deaths in the UK have been poorly attended by MPs, despite increasing evidence that covid hospital and care-home protocols were dangerous or potentially fatal – and that vaccine injury is real. The suppression of alternative views has been an enduring feature of both the response to the opioid and covid crises.

I left academia in 2018, after 10 years teaching/researching the history of medicine. I had many happy years in HE; however, from around 2012/13, I sensed that things had begun to change. I’m sure those changes were decades in the making, but I was too optimistic to notice. Eventually, I realised there was something ironic about working on a large interdisciplinary research project entitled ‘Lifestyle, health and disease’ , funded by the Wellcome Trust (which purports to exist ‘to improve health for everyone’) while simultaneously recognising that the agendas of academia and ‘global health’ are compromised beyond repair. I felt like I’d been shuffling the deckchairs on the Titanic for rather a long time. Life has been challenging since speaking out about the world of history, medicine, big pharma and academia. I have lost many former professional colleagues, but gained a new family of clinicians, academics and professionals prepared to speak openly, and who are committed to writing a new and more honest playbook to confront the challenges we now face in science and medicine in the years to come.