The most vulnerable still suffering from inhumane policy decisions

I am a community registered nurse. During the two major waves of the UK’s epidemic I was regularly sent to care home residents who were diagnosed with Covid or who were isolating due to potential exposure to Covid. My experience is that some of the policies put in place to protect care home residents, although possibly well intentioned, were in fact harmful to them.

Small but frequent drinks

We all know that the frail elderly require sips of fluid little and often. They do not drink a glass of water all in one go, instead, small sips need to be offered, on a regular basis throughout the day. Little but often. Anyone who looks after a frail elderly person knows this.

Furthermore, some elderly people can also lose their thirst sensation, especially those with dementia, and so regular encouragement of drinks is essential. And some care home residents not only need prompting, but require full assistance to physically lift the beaker to the mouth. A large proportion of care home residents are entirely dependent on staff to keep them hydrated, whether it be prompting or physically assisting with drinks.

Yet the Covid policies implemented in care homes since spring 2020, specifically

(1) isolation and time consuming PPE requirements

(2) visitor restrictions

have had a direct negative effect on the amount of fluid offered and consumed, leading to an increase in dehydration among care home residents, and is consistent with reporting in the British Medical Journal stating that “Neglect, thirst, and hunger were—and possibly still are—the biggest killers”.

Isolation and time consuming PPE requirements

Residents were required to isolate in their room for 14 days (which was reduced to 10 days in December 2020) if they received a positive PCR test. This period of isolation was also required for any resident that left the care home for any reason (for example going to a hospital or clinic appointment) even if not testing positive.

This isolation policy was put in place in order to keep the other residents “safe” — and may have had merit. However, evidence is scant on whether it did actually reduce transmission, particularly when implemented in buildings with poor ventilation. It was also not without serious consequences for the resident in isolation.

During this time of isolation, the staff are required to put on (don) personal protective equipment (PPE) whenever entering the room, and remove (doff) on exiting from the room. Anyone that works in healthcare will know that donning and doffing PPE is very time consuming, with a specific order to it that requires sanitising hands in between certain stages of the process. It takes a considerable amount of time when done properly.

Care homes are incredibly busy places, with enormous demands placed on the staff, such as washing residents, toileting them, dealing with incontinence, assisting with medications, assisting to feed residents, mobilising, hoisting, repositioning, assisting with confused residents. The list of minor — but important — tasks is essentially endless. The resident to staff ratio in most care homes is extremely challenging at the best of times. Expecting staff to don and doff PPE each time they enter the room of the isolated resident puts them in an impossible situation. Staff time is an extremely limited resource, and allocating it to one care task inevitably results in sacrificing an alternative care task. The harsh choice was often — do they break the strict PPE requirements to offer sips of fluid frequently (as they would have done pre-pandemic), or do they limit the amount of times that they enter the room.

I doubt that it was a conscious choice — rather than omit the PPE requirements (resulting in certain disciplinary action if caught) instead they had to drastically limit the frequency that they entered the room of any isolated resident (there would be no disciplinary action for this). In care homes with staff shortages and competing demands, government policy still had to be followed, to the detriment of basic care needs — the staff had no realistic alternative. In my experience, this resulted in residents having less access to regular small drinks.

Visitor restrictions

This situation was made even worse by the ‘no visitor’ policy that was in place. In pre-pandemic times there would be a steady flow of visitors, ensuring that residents were assisted frequently with small drinks. Visitors have always been a godsend for care homes, as the visitor is able to sit with the resident, and encourage or assist with drinks, little but often, over their visiting period. Although not every resident has visitors, many do, and for those that do, this can free up staff to focus more on those that do not.

However, since spring 2020, there have been long periods with strict policies restricting visitors to care homes — in order to “protect” the residents. In my experience, this has resulted in residents having less access to regular small drinks. Furthermore, it also resulted in increasing the number of tasks required to be performed by staff, since some residents’ care needs were no longer being met by visitors. This increased staff workload further, in an environment where they were already overstretched.

A disastrous combination of policies

In combination, the above policies have significantly limited the access to human contact for care home residents, whether it be from staff members or visitors, and inevitably this resulted in the omission of frequent sips of water. I have lost count of the number of residents that I attended to, who had a dry mouth and were thirsty. They would drink sips of fluid when I offered it. They had a reduced urine output. The isolating residents that I took blood from (as requested by the GP) were almost invariably found to have impaired kidney function (raised blood urea and creatinine levels), often with high blood sodium levels (hypernatremia). They were clinically dehydrated. And I must emphasise, these were not palliative patients in their “terminal phase” (when the body shuts down and fluid intake naturally ceases). These were patients that were conscious, sitting up talking with me, but significantly dehydrated.

In my experience, in the numerous care homes that I visited as a community nurse throughout the two major peaks of the pandemic, these policies resulted in less access to regular drinks. The impact of reduced fluid intake for the frail elderly cannot be overstated, most of these residents had a rapid clinical deterioration. I cannot speculate what their prognosis would have been without the policies in place, but what I can say for sure is that Covid did not cause their dehydration — that was entirely a consequence of policy decisions: it was a policy-driven harm.

I must emphasise that I am sharing my personal experience as a community RN, in one district of the UK. I am not generalising or stating that this was a universal experience for all care homes. But we need to speak to care home staff, residents and relatives, and determine whether my experience was unique, or was it commonplace. Crucially, staff need to be free to voice their criticism and concerns — as there is much fear amongst healthcare workers about speaking out against government policies.

Solutions

So what is the solution? At the very least there is a requirement for an honest review and open discussion. We must learn from mistakes made so that we can help shape future policies for highly vulnerable people. Otherwise we run the risk of the same destructive policies being implemented again in the future.

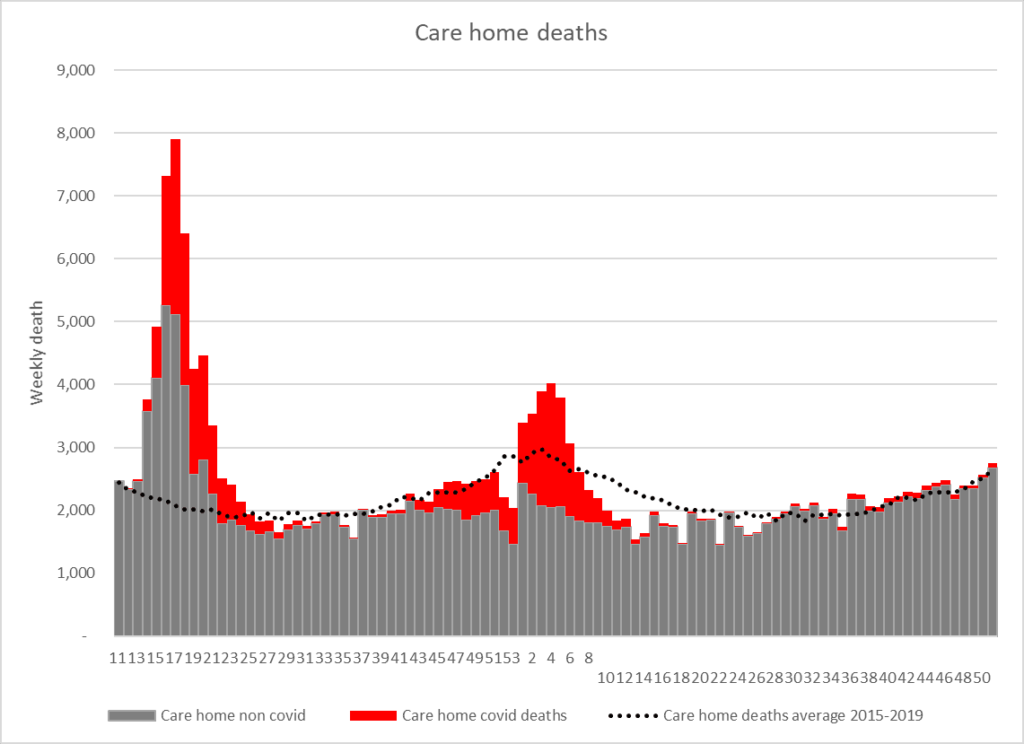

We need a review of the deaths in care homes. Care homes saw a surge in excess deaths in the first few months of the pandemic, a high proportion of which were non-covid deaths.

What caused those excess deaths? What factors led to the clinical deterioration? This research will be no easy task, as it will always be difficult to disentangle which deaths were due to natural disease progression and in which dehydration played a significant part.

I have no doubt that the policies of isolating vulnerable patients, the PPE requirements, and the restriction on visitors, were all well intentioned. However, it is also abundantly clear that these policies were extreme to the extent of being damaging. I also have no doubt that they resulted in serious negative consequences for the hydration status of so many of the residents. This is in addition to the obvious effects of mental wellbeing, especially for dementia sufferers.

Was it not possible to use the Nightingale hospitals as Covid convalescent hospitals, to place the PCR positive residents, rather than isolate them in their rooms? They then would have been able to receive more dedicated care, and this level of care would not have required particularly skilled staff. Volunteers and redeployed staff could easily have managed this, which would have given a very favourable staff to patient ratio. Obviously, any staff working there would need to be deemed low risk (or Covid recovered).

And for the other care home residents, was it not possible to allow an elected family member or friend that could have continued to visit? Would that have put the residents in any more danger than the staff that come in and out of the care home each day? I met many relatives that would have been committed to shielding in between care home visits, in order to be able to continue seeing and helping their loved one. The benefits of this would have been substantial.

I am sure there are many other interventions that could have been implemented to enable focused protection of the vulnerable care home residents. What I find difficult to stomach is that hundreds of billions of pounds has been spent on the UK Covid response, yet very little of that has been spent on the care homes — the very place where almost a third of the Covid deaths occurred.

Why am I sharing this now?

Up until now I have been reluctant to share my experience publicly. I do not want care home staff to take blame unfairly, as to expect them to have done any differently would be to expect them to incur disciplinary action.. Care home staff are amongst the hardest working people I’ve ever come across — they often stay late, unpaid, to complete their tasks. But they can’t do the impossible, and they have been expected to do exactly that. Criticism needs to be directed at the policy makers, not at those working tirelessly on the ground.

In my opinion, the policies of isolating vulnerable residents in care homes, the time consuming PPE requirements and the restriction on visitors within care homes were a terrible mistake, and should not be implemented again. In my experience, these policies in care homes have been responsible for causing significant dehydration, and accelerating the clinical deterioration of many vulnerable residents. These policies have caused great harm to the very group that they were supposed to protect.

I am choosing to remain anonymous due to the professional backlash that I could face in this current climate. I — and many healthcare workers I know — are fearful to speak out publicly and too scared to raise our heads above the parapet. But I share my experience here as I hope it can be a contribution to this important and long overdue national debate.

Please also read the detailed report from Collateral Global and accompanying editorial.