Lockdowns can work for some infectious diseases, but not for COVID-19

When a disease is transmitted in a chain person-to-person, as for childhood infections such as measles, then reducing human contact reduces transmission. The data on gastroenteritis shows clear evidence of this. Most gastroenteritis is caught through close contact.

Google publishes data on phone tracking which follows people in retail, recreation, public transport and workplace settings (among others). This Google mobility data is a good surrogate marker for how much people are interacting. People travelling to retail, recreation, work or stations dropped by 70% in March 2020. Attendances for gastroenteritis at the emergency department halved in March 2020 and the attendance rates have correlated very tightly since.

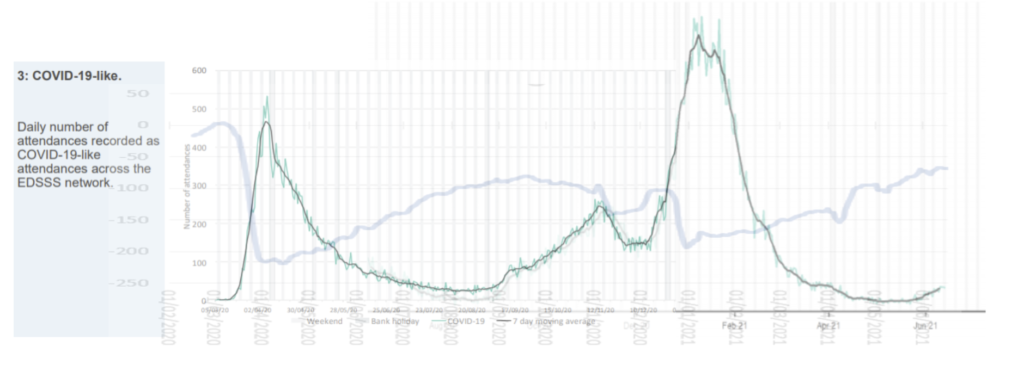

However, the same data does not show a similar relationship to COVID attendances. Seasonal infectious diseases, like influenza, show winter surges are unrelated to human behaviour and low levels of transmission in summer, again, are independent of human behaviour. COVID-19 appears to have a similar trajectory unrelated to changes in human interaction. Influenza surges occur in a dramatic but predictable and seasonal way.

Government modellers continue to assume a measles type model for predicting COVID-19. Hospital admissions have flatlined at about 200 a day for the last seven weeks but SAGE predicted they would be 600 a day by 26 June. Continuing to model COVID-19 as if behaviour affects transmission is proving to be wrong yet again. A combination of seasonal susceptibility and aerosol transmission over large distances are likely contributors to spread and lockdowns would have no impact on these factors. Ending lockdown last summer resulted in no rebound after VE day, protest marches and crowded beaches in the UK. The predicted rebound due to opening up of schools in March 2021 in the UK also doesn’t fit the model and the US states where citizens are living free without restrictions are seeing no negative consequences.