Hurricane Katrina and the Angels of Mercy

By Jonathan Engler (co-chair HART) and Jessica Hockett (see substack here)

The debate as to how much “pandemic” harm was caused not by a virus, but rather by the dystopian response to the perceived threat of a virus, has been raging for some time now.

Jonathan tweeted about this last year in relation to Lombardy and that thread was turned into this Panda article.

An analysis of the spatial characteristics of deaths during the spring 2020 wave in Northern Italy was carried out by him along with a Panda colleague; this suggested that it looked nothing like a spreading virus, and more like the sudden imposition of a policy response.

More recently, Jessica has essentially come to the same conclusions about New York: that something terrifyingly unnatural appears to have happened, which cannot be explained by the sudden spread of a deadly virus.

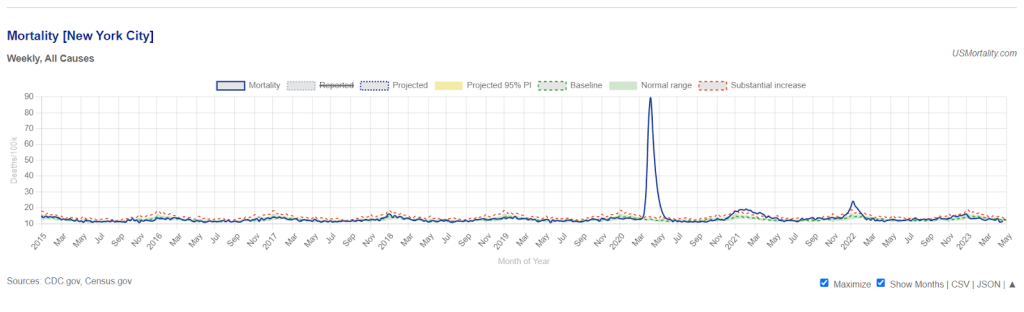

It surely does not require any scientific understanding whatsoever to glance at the below graph of total mortality rate in NYC going back to 2015 and see that what happened in a few weeks during spring 2020 suggests an abrupt episode of ferocious lethality which was at odds not only with anything observed anywhere at the time or thereafter, but also with even the highest estimates of the infection fatality rate alleged to have caused “the pandemic”.

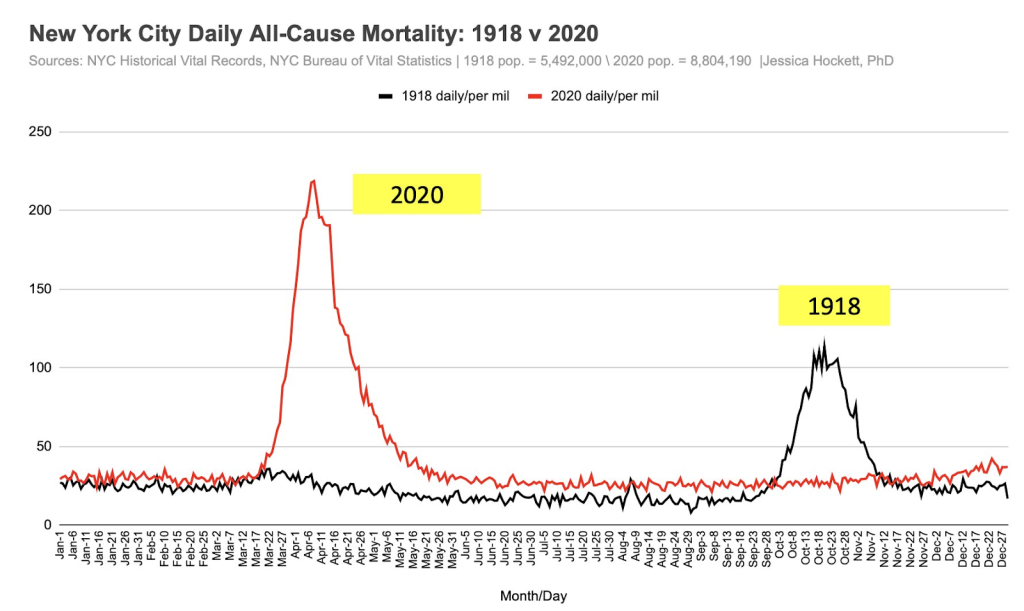

If we look back even further, it can be seen that the reported spring 2020 mortality spike in New York is actually around double that observed in the autumn of the 1918 pandemic. But other places in 2020 did not see waves of deaths anywhere near those observed during the 1918 pandemic.

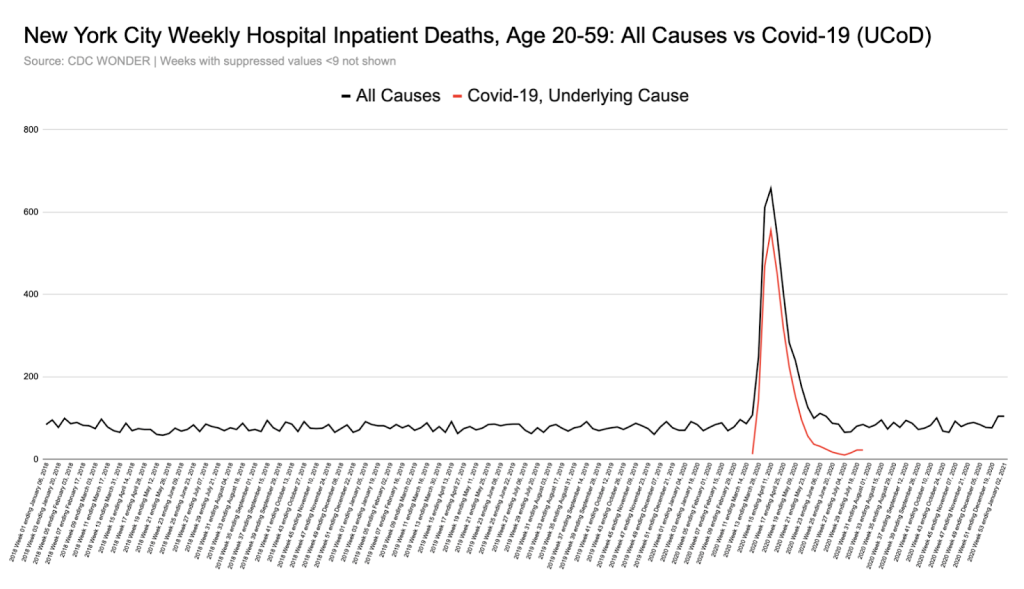

Moreover, unlike elsewhere, the increase in deaths was seen across a younger demographic, not exclusively in the elderly.

As shown in the graph below, all-cause hospital inpatient weekly death counts in the 20-59 age group were dramatically elevated for a short period, by a shocking 6-fold at their peak, with nearly all these deaths being coded as ‘covid’.

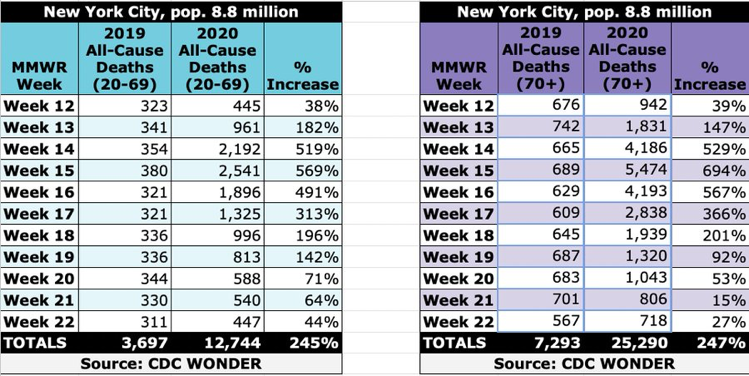

In fact, in New York, the % increase in all-cause deaths during the spring “1st wave” period was the same in the 20-69 year old age group as in the 70s and over:

In other places, however, what we were told was the same disease caused by the same virus left the younger age groups largely untouched, with nearly all deaths being in the elderly.

This discrepancy remains completely unexplained. It seems unarguable that certain difficult questions certainly need asking about what happened in New York in 2020 if we are to unravel the truth about what happened there.

Of course, the narratives emerging from Northern Italy and New York in 2020 were instrumental in driving fear and hysteria worldwide. Moreover, the number of deaths in both places informed early estimates of the IFR. These inciting incidents directly sparked much of the worldwide exaggerated, fear-driven response to what we now know was (if anything) a virus mainly affecting the frail and elderly, to which most people already had sufficient immunity to prevent severe illness.

For these reasons, it is essential that particular attention is paid to try to ascertain precisely what happened in these specific places.

It’s worth detailing – as evidence for the deeply dystopian mindset operating at the time – just some of the many deviations from normality that adversely affected human health and immunity, or which constituted sudden changes to healthcare practice.

These included (but were not limited to):

- Stress and anxiety from confinement (being told to stay home) and fear propaganda

- Discouragement to attend hospitals if ill

- Reduced community prescribing of broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Low staff levels in healthcare settings due to self-isolation of those “testing positive,” even with no symptoms

- Isolating the elderly

- Barring loved ones from hospital and care homes

- Fear (on the part of HCWs) of tending to covid positive patients, compromising basic medical and care needs.

- Early and inappropriate invasive ventilation

- Overuse of midazolam and opiates

Inevitably, and rightly, some researchers have started to perform post-pandemic autopsies analysing the motives and reasoning used to justify policies and other changes in behaviour and to examine their real world consequences.

Some medical practitioners have taken umbrage at any suggestion that the stressful environment and sudden expectations and pressures laid upon them may have resulted in well-meaning medical staff crossing ethical lines, or violating the Hippocratic Oath.

Those who wish to point out that there is historical precedent for medical staff behaving diabolically while thinking they are doing good often invoke atrocities during the 1930s and 1940s (and receive opprobrium as a result).

However, there is a much more recent example, and one which we were oblivious to until recently, despite this incident being totally “out in the open”, the subject of a lengthy investigative article, book, and a TV mini-series: the post Hurricane Katrina incident at Memorial Hospital Center in New Orleans in 2006.

Wikipedia provides the basic facts:

In the hurricane aftermath, the basement of Memorial Hospital Center flooded, power failed, and battery power for essential equipment started to run out. Most, but not all, patients were successfully evacuated.

The hurricane occurred on 29th August. A shocking finding was made in the aftermath, as described in the Wikipedia article:

On September 11, mortuary workers recovered 45 bodies from the hospital. Toxicology tests were performed on 41 bodies, and 23 tested positive for one or both of morphine and the fast-acting sedative midazolam [branded as Versed in the US], although few of these patients had been prescribed morphine for pain.

In the following weeks, it was reported that staff had discussed euthanizing patients. Some reports went further; Bryant King, an internist at Memorial, told CNN that he believed “the discussion of euthanasia was more than talk.”

LifeCare told the state Attorney General’s office that nine of their patients might “have been given lethal doses of medicines by a Memorial doctor and nurses.”

King publicly charged that one or more healthcare workers had killed patients, based on conversations with other health care workers. King told CNN that when he believed a doctor was about to kill patients, he boarded a boat and left the hospital. King explained his actions in terms of his opposition to Pou’s alleged actions, arguing “I’d rather be considered a person who abandoned patients than someone who aided in eliminating patients.”

Following an investigation into the deaths described above, the local DA (“District Attorney”) decided there was sufficient evidence to charge three medical staff with four counts of second-degree murder. Charges against two were later dropped in exchange for testimony.

The prosecution was deeply unpopular. Despite substantial evidence of deliberate actions taken to terminate lives – indeed, enough to satisfy the legal definition for homicide – many members of the public felt medical staff were simply “doing their best” under very trying circumstances. According to a local reporter the incident “ignited a furious debate in New Orleans and elsewhere about whether sharp ethical boundaries can be drawn around decisions on patient comfort made in a crisis.”

The DA failed to win re-election, and when the new DA convened a Grand Jury* at an undisclosed location, much of the previously amassed evidence was not presented and some of the key witnesses not called. The Grand Jury decided that charges should be dropped.

Unsurprisingly, several commentators (e.g., Loyola University Law Professor Dane Ciolono) opined that the Grand Jury was convened and run in such a way as to ensure charges would be dropped while providing “cover” for such an outcome.

Whatever actually occurred at Memorial Hospital, or whatever the staff’s motives, the incident speaks to an unsettling, yet undeniable truth: during a crisis, “ethical red lines” – however deeply held and valued – may be easily crossed. Society may judge those decisions acceptable or understandable, as appears to have happened with the Memorial Hospital case.

In summary, it would appear that the legal process was manipulated to assure an outcome which accorded with public opinion – that is to say to extinguish the possibility of prosecution while maintaining the pretence of due legal process. In this way, facing up to the stark reality – that as a society we mete out justice arbitrarily when we wish to – was avoided. Perhaps the well-ordered rules-based system suggested by statutory definitions of what actions constitute crimes, is to some extent just “for show”.

The Memorial Hospital case obliterates – with a relatively recent example – the notion that doctors and nurses all have the same ethical boundaries which they simply will not cross under any circumstances.

Could such boundaries have been crossed during the recent covid event?

A number of commentators are considering the possibility that changes in the policies and practices around the use of certain drugs (midazolam and opiates), and procedures (invasive ventilation) – sometimes in combination – may have contributed to the high mortality reported, at least in some specific places.

In relation to drugs, in an article published on his Substack last year, the blogger known as Bartram’s Folly explored the possibility that (in the UK) sheer fear and panic may well have driven medical staff to use midazolam and opiates more liberally in patients with covid, which may have encompassed anyone with a positive covid test.

In the UK one such mechanism which may have encouraged this measure is the NICE Guideline NG163 (no longer on their website but available here or as PDF download here), about which others have also written in detail. This guideline effectively transposed the advice for treating end-stage cancer patients with midazolam and opiates into that for covid patients.

HART has written about NG163 before; in its latest piece, we point out how embedded it was into treatment protocols. The message – included in training material – is very much that carers should “not be afraid to prescribe in line with patient’s requirements”, with no warnings or concerns expressed about the possibility that midazolam and morphine might reduce respiratory drive when used to treat breathlessness in covid patients.

Of the guideline, Bartram said,

“…the NICE guidelines appear to have introduced a pathway for doctors which allowed for (perhaps even encouraged) more than a gentle nudge for those who were ill with Covid towards death, some of whom might well have survived given the chance. This iatrogenesis hypothesis would mean that at least some of the deaths recorded as with Covid might well have been a direct result of the care guidelines as set out by NICE.“

Later, Bartram makes the point that the pretext of a crisis situation or emergency may establish the grounds for ethical boundaries to be crossed or disregarded, at least temporarily, under the auspices of ignorance or ‘doing one’s best’ with the information said to be known or available at the time:

It is important to note that in the iatrogenesis hypothesis it isn’t necessary for some people to have had an evil intent – it is entirely possible that individuals promoted and exercised a policy that resulted in needless deaths while believing that they were ‘doing the right thing’ (e.g., see Hannah Arendt’s concept of the banality of evil).

In particular, ‘petty bureaucrats’ appear to be readily able to think up policies without seeing the need to consider the full consequences, and when these consequences are eventually revealed will usually point to the minutes from endless meetings with other petty bureaucrats to show that they weren’t personally responsible for the policy and they were simply following process.

Of course, once a framework had been decided front-line staff might have been grateful for the guidance offered given the challenging times, at least until the negative consequences of the guidance became painfully clear.

It should also be remembered that – in the US at least – certain extraordinary policy measures may have been important factors. For example, during the emergency NYC Governor Cuomo issued executive orders and suspended laws which gave doctors and nurses immunity and absolved hospitals of the responsibility to keep close patient records. (The order itself can be found here, and some legal commentary on it here.) Articles in JAMA can be interpreted as giving ethical permission for physicians to issue unilateral DNR orders, avoid CPR, and ration ventilators and critical care beds.

Moreover there are numerous examples of doctors, nurses and others in the US who later said they were following guidance, learning as they went. (See this interesting essay by Dr Kory, for example.) Under these circumstances it is easy to see how they could assume that something which ordinarily might have been questionable would become acceptable as “everyone else was doing it”.

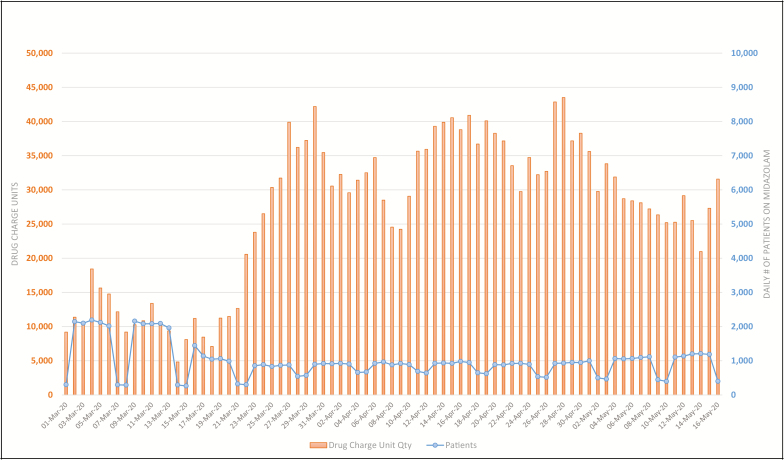

Evidence of increased midazolam use can be seen in the US as well as in the UK. This graph from a study describing the use of 7 specific drugs in 47 hospitals in NY shows the daily count of patients (blue) who received midazolam and the disproportionate quantities used (orange) between March 1 and May 16, 2020.

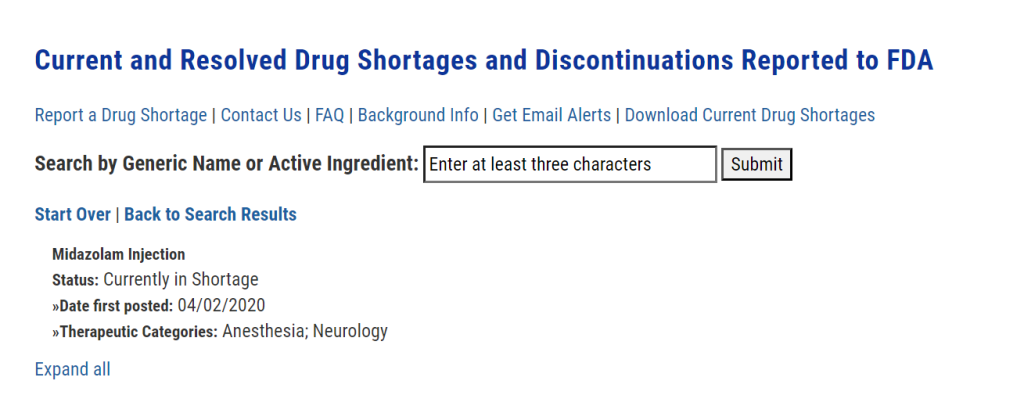

Moreover, midazolam is currently listed by the FDA to have been in short supply since 2 April 2020:

This Guardian article from 13 April 2020 reports on a letter sent by “a group of prominent medical practitioners and experts” to capital punishment states imploring them to:

“release their stocks of essential sedatives and paralytics that they hoard for executions” so that they can be “used for intubations and mechanical ventilation of the most severely ill coronavirus patients who cannot breathe for themselves”.

The tone of this letter can be taken to illustrate the sense of sheer panic prevailing at the time – certainly not conducive to rational decision-making – combined with the assumption that invasive ventilation was going to be extensively required and used.

This takes us to the question of invasive ventilation, whether it might have been used too often, inappropriately, and why.

As well as panic, the role of fear on the part of healthcare workers cannot be underestimated. Here is Dr Vinay Prasad stating that:

“It is a unique situation in medicine. In our whole medical career, doctors have never been personally afraid the way they were [with covid].”

Official guidance (see for example this from a British anaesthetists’ professional association) certainly reinforced the idea that one of the benefits of early intubation was to reduce the aerosolization of virus, such that it would be safer for those caring for the patients, compared to when non-invasive forms of ventilation were used.

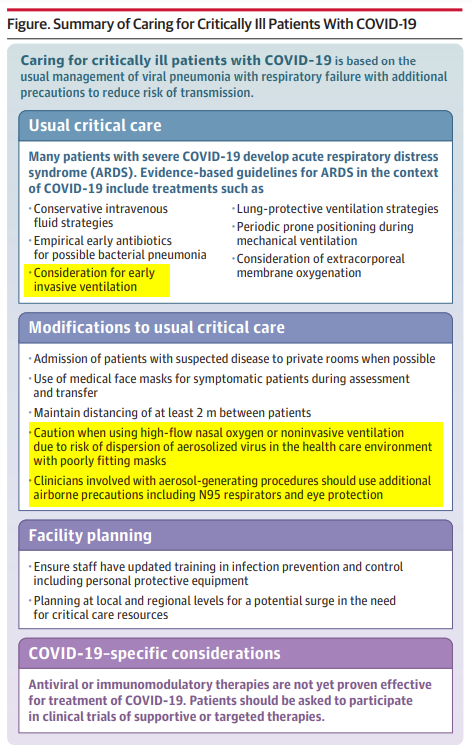

This JAMA Clinical Update “Care for Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19” published on 11 March 2020 strongly supports the idea that the thinking was very much that non-invasive oxygen augmentation could be dangerous for healthcare workers:

The journalist Alex Berenson was early to point out that ventilator shortage may have more to do with overuse “to protect staff” than to being overwhelmed by patients in respiratory failure.

It seems like fear may well have been augmented by official guidance to result in significant overuse of this measure.

It is important to understand the differences between the Memorial Hospital incident and what may have happened in the early stages of the covid crisis. In New Orleans, it may indeed have been reasonable to assume that it was going to be impossible to evacuate the patients (who were given midazolam and opiates to ease suffering) in time, and that they were indeed unsaveable due to the extraordinary circumstances. (Whether or not this was actually the case will probably never be known, because of the legal shenanigans described above.)

However, whether that applies to all, some, or just a few of those who died in spring 2020 after being administered the same or other drugs (or placed on mechanical ventilators or issued a unilateral DNR, etc.) is still a matter of debate whereas for sure, Hurricane Katrina was self-evidently an extreme weather event that created devastation and emergency conditions in its fury and wake.

Certainly, it seems clear that personal fear and a belief in the lethality of this infection drove much medical decision-making in the early days. It is not hard to imagine actions being taken which were then rationalised by imagining the suffering that had been prevented, limited resources preserved, and many lives saved. The deaths witnessed could easily have acted as positive reinforcement in the minds of healthcare workers as to how serious the illness was. These protocols could lead to the deaths of patients who were not particularly old and frail and thus reinforce the message that the virus was potentially fatal even in such people

The decisions that healthcare workers made, and the influences on and factors involved in those decisions, will be discussed and dissected for decades to come. When humanity is ready to confront what occurred – and admit that ethical inversions in hospitals and care homes contributed to unintentional iatrogenic death, we can move toward keeping it from happening again.

* (A Grand Jury in the US is a specific type of court empowered by law to determine whether probable cause exists to support criminal charges for a suspect in a crime. Louisiana – in which New Orleans is situated – is one of 23 US states that use grand juries for indictments in serious crimes.)