A detailed look at the legalities

Guest author, Philip Ridley has thoroughly researched the legalities surrounding the Court of Protection vaccine rulings for autistic and mentally handicapped adults and whether they are in fact lawful.

We hope his deep dive into this topic may be of use for those faced with similar issues. It was sent to us by Charlie’s mum, who you may remember is involved in an ongoing battle for her adult severely autistic son.

Introduction

The Court of Protection (the Court) has been gratuitously overreaching its authority on societies’ most vulnerable adults who lack mental capacity, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. This article explores the ways in which the Government and Courts could together be acting unlawfully when it comes to parental rights, very much to the detriment of these individuals and their families.

In the article we cover both the role of the Court of Protection and whether it should interfere with the exercise of parental responsibility and also with the responsibilities of deputies or those with lasting power of attorney. We also cover the out-dated approach to informed consent that the court is using and suggest that the Mental Capacity Act prohibits most use of experimental medicines, such as Covid-19 vaccines, on people who lack capacity.

Adults who lack mental capacity are particularly vulnerable to arbitrary medical policy, including for vaccination and testing. Never has this been more starkly exposed than with regard to the Covid-19 programme. To date, and with only one exception, the Court of Protection has mandated the vaccine on all adults who do not have mental capacity, disregarding strong objections from close family members. The sole successful case hinged upon the individual having objected to vaccination prior to losing capacity.[1] This argument is unlikely to protect most who have lost their mental capacity, since many in the general public fail to create a living will making an advance decision to refuse treatment. It also leaves vulnerable most young adults without mental capacity because in all likelihood, they never had capacity in the first place.

The behaviour of the Court raises essential questions around both parental rights in relation to parents exercising their responsibilities for an adult child who lacks mental capacity, particularly when capacity has never been attained and also rights for those who exercise lasting power of attorney. The Court’s behaviour raises serious questions around the test of materiality with regard to material risks to be considered when providing informed consent for said adult.

Informed consent

First, let’s look at the outdated approach to informed consent being imposed by the Court of Protection and likely other courts such as the family courts, when considering the best interests of a person who lacks capacity. The Court’s approach to the material risks of medical treatment, including the risks of not having treatment, appear to involve slavishly following recommendations from doctors who advocate for the “responsible body of medical opinion” known colloquially as “the science”, as defined by government policy.

In doing so, the Court will disregard the views of parents, other next of kin, deputies and people with lasting power of attorney, even to the point of disregarding the views of other highly qualified experts who have the audacity to disagree with government policy.

The first problem with this is constitutional. It was established by the Kings Bench in 1610 with the Case of Proclamations[2] that the law of England is comprised of “common law, statute law, and custom” as is reflected by the Coronation Oath[3]. Crucially, the court declared in what remains the leading case on proclamation, that “the King’s proclamation is none of them”. Government guidance is therefore a form of proclamation by HM Government that is not law. Government guidance on whether a medicine should be had or not be had should therefore be treated as hearsay evidence in court to allow expert witness clinicians on both sides of the argument to have due process of law[4], but this simply does not occur; the clinician who supports the government position wins every time as if this were a Medieval star chamber controlled by the King, or a Soviet court under the control of the ruling Party Chairman.

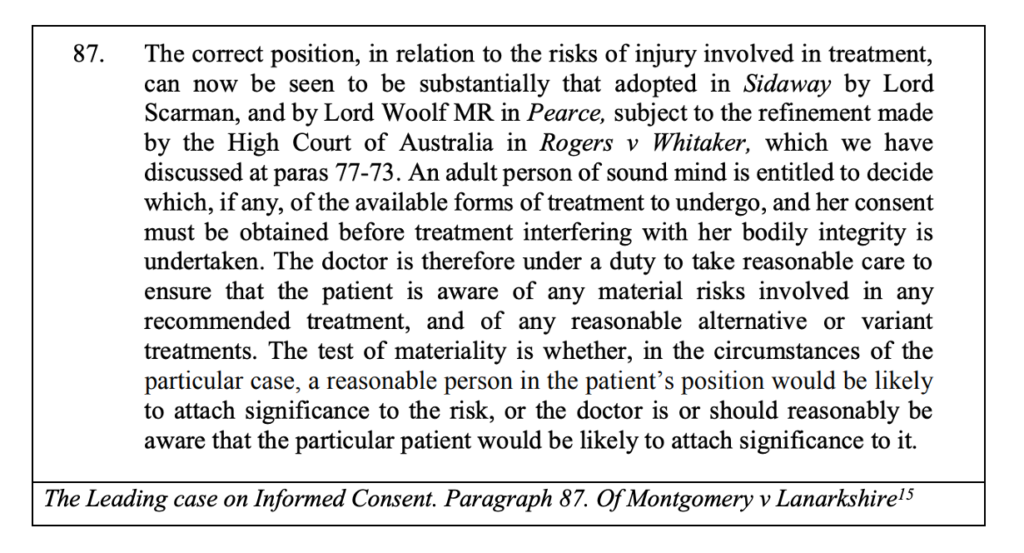

The second problem is that the court’s current approach of generally defaulting to “the responsible body of medical opinion” reflects an extreme and likely unlawful interpretation of the outdated Bolam Test,[6] which the Supreme Court repealed in 2005 in Montgomery’s case for the purpose of the duties involved in providing informed consent. In this case the UK’s Supreme Court adopted the position taken by the Australian High Court in Rogers v Whittaker,[7] that the test of materiality when considering the risks of having or not having a medical intervention is whether “in the circumstances of a particular case, a reasonable person in the patient’s position would be likely to attach significance to the risk.” The patient may well carefully consider government guidance on the matter but they are perfectly entitled to disregard it.

If this correct approach to law was applied by the Court in best interest cases, this ought to be amended to recognise whether in the circumstances a reasonable person in an “Interested Person’s” [8] position would be likely to attach significance to the risk, be it the parents, next of kin, deputy or lasting power of attorney, etc., taking into account what the patient would be likely to consider if they had capacity. The current situation has the absurd position of requiring that interested persons are consulted, raising their expectations that they can discharge a responsibility to make decisions on behalf of the person, with them being over-ruled should they be bold enough to disagree with government guidance.

It is likely that GP’s, local authorities, carers and the Court default to the out-dated and now unlawful Bolam Test, blindly following “the science”, not in the best interest of the individual, but so as to avoid risk of liability. Yet clinical negligence will occur if the duties set out in Montgomery’s case are not discharged. This is precisely why the balance in decision making must shift towards “Interested Persons” and parents in particular, with Montgomery’s case being asserted in court and in campaigning for reform.

Experimental medicine and capacity

A material risk that courts have refused to take seriously is the experimental status of COVID-19 testing and injections, none of which have complete clinical trials until 2023. One judge went so far as to erroneously state in their ruling that Covid-19 vaccines are no longer subject to clinical trials, yet all Covid-19 tests and injections continue rely on emergency use authorisation alongside ongoing clinical trials at this time.

The 2005 Mental Capacity Act has stringent safeguards against “research projects” affecting people who lack capacity[9]. With “research project” having no express definition in either the 2004 Clinical Trial Regulations or the 2005 Mental Capacity Act, we can only conclude that Parliament consented to the widest possible interpretation that must go beyond clinical trials to include medicine under emergency approval that is subject to various “research projects”.

The UK Health Security Agency’s ongoing COVID-19 vaccine surveillance project is surely a research project for the purposes of the 2005 Mental Capacity Act.[10] It involves “detection and evaluation of possible adverse events associated with vaccination” and enhanced surveillance of vaccine failure. Whilst the JCVI has concluded that the vaccines are safe and effective, this is clearly an interim position in connection with ongoing clinical trials “undertaken in ideal delivery conditions” tending to “exclude certain populations, such as individuals with underlying medical conditions” that “typically have a relatively short follow-up period” alongside ongoing “real world” post intervention surveillance (research projects) such as the surveillance project, that the government believe to be “required to monitor delivery of the vaccination programme and evaluate its impact on health”.

If the Court accepts that these “real world” post-intervention surveillance systems being carried out in parallel with ongoing clinical trials constitute “Research Projects” in any way, then it must be unlawful for persons who lack capacity to be subjected to them because they fall into a category that is expressly excluded by the Mental Capacity Act. It only allows for research projects related to an “impairing condition”, which means a condition which is (or may be) attributable to, or which causes or contributes to (or may cause or contribute to), the impairment of, or disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain. Even then the research project is only lawful if it cannot be conducted on people who have capacity.

In any case, s.32 of the Act requires that interested persons are identified and that any research project does not occur or is abandoned if an interested person states that in their opinion the person’s wishes and feelings would be likely to lead to them declining to take part in the project if they had capacity in relation to the matter. Sadly, none of the best interest cases regarding Covid-19 injections have addressed the research project sections of the Act.

The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004 set out Parliament’s position on consent for clinical trials and this should be taken into account when considering research projects. Part 2 of Schedule 1[11] states that “Clinical trials shall be conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki[12], and that are consistent with good clinical practice and the requirements of these Regulations.”

Part 5 of Schedule 2[13] then covers conditions and principles which apply to clinical trials in relation to an incapacitated adult. Amongst other things they require that the legal representative provide informed consent on behalf of the incapacitated adult, which can only mean discharging the duties set out in Montgomery’s case. They must also, without detriment be informed of the right to withdraw from a trial at any time. It is surely detrimental to be subjected to a best interest court case as a result of withholding consent, raising wider ethical issues around the Court of Protection’s approach to mandating COVID-19 testing and vaccination.

Clinical negligence could be a reason why the Court of Protection is not authorised to interfere with parental responsibility. This is because notwithstanding a court decision, a parent could sue the clinician who seeks to administer a treatment for the tort of clinical negligence if informed consent has not been obtained. Where the Court of Protection has only considered the “responsible body of medical opinion”, clinicians could be vulnerable to challenge, particularly if we can prove that the court order relates to a decision excluded by s.27 of the Act. Where persons who lack capacity are subjected to an unauthorised and therefore unlawful research project, the necessary consents will not be in place and the clinician or responsible medical officer could be liable for the tort and crime of battery.

This would not be the first time that the Court of Protection has been found to exceed its authority. Caroline Hopton, Simon Mottram, and Rosa Monckton successfully challenged the Court’s policy of a presumption that deputyships will only be approved in the ‘most difficult’ cases. No such presumption can be found anywhere in the Act and guidance cannot lawfully create any presumption not found in Common Law or express statutory provision. This is however precisely what they did until a group of mothers bravely challenged the Court in their children’s best interest.

Jurisdiction of the court protection

There is common ground in that s.27 of the Mental Capacity Act (2005) (the Act), prohibits the Court of Protection from interfering with the exercise of parental responsibility for a child under the age of 18 who lacks capacity, except regarding the child’s property or where the court rules that the parent lacks capacity.[14]

However, parents often retain substantial responsibilities after their child reaches the age of 18, yet the Court claims that they can ride roughshod over any rights that the parents have to continue to exercise their Common Law responsibilities – simply because their child has reached the age of 18. Some go so far as to say that parental responsibilities and rights end entirely on their child’s 18th birthday. As a result, parents who retain caring responsibilities can even be denied access to medical records relevant to the individual’s care. This surely cannot be in the adult’s best interest and results in significant distress for parents, whose uppermost concern is the wellbeing of their adult child.

A similar unconstitutional situation has occurred regarding parental responsibility for adults who lack mental capacity. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 Code of Practice[15] states that “Nothing in the Act permits a decision to be made on someone else’s behalf on any of the following matters: (including) “discharging parental responsibility for a child in matters not relating to the child’s property”.

However, the words “for a child” cannot be found in s.27 of the Act regarding “excluded decisions”, which actually states that the Court cannot make a decision on someone else’s behalf regarding “discharging parental responsibility in matters not relating to a child’s property”. The Act states “not relating to a child’s property” whilst the guidance states “not relating to the child’s property”.

The Court of Protection will likely claim that this is because s.50 of the Act[16] brings the interpretation of “parental responsibility” in line with s.3 of the 1989 Children Act for the purposes of the Mental Health Act,[17] meaning that parental responsibility and therefore parental rights only apply in that context to children under the age of 18. However, if the statute is read correctly then this cannot also be true for s.27 regarding excluded decisions. This is because the Children Act interpretation of “parental responsibility” is only found within and therefore only applies to s.50, which relates solely to whether permission is required for an application to the Court.

Had Parliament consented to the Children Act definition of parental responsibility applying to s.27 regarding the jurisdiction of the Court, we would also see it in s.64 (General Interpretation)[18] or in s.27 itself, but it is nowhere to be found in these sections of the Act. As a result, the only possible interpretation of the statute is that Parliament consented to the Children Act definition of parental responsibility applying in s.50, regarding whether permission is required for applications to the Court, with the broadest possible definition including parental responsibility for adults 18 years and above applying to s.27 regarding excluded decisions.

This approach to parental responsibility is after all the one taken by health and social services when it suits them, i.e., when parents agree with the “advice” that has been given. This is because parental consent for an adult who lacks capacity will generally be accepted as providing adequate lawful authority for medical treatment except where the parent has the audacity to go against the “responsible body of medical opinion”. It is therefore often the case that these best interest cases do involve making a decision regarding the discharging of parental responsibility and we believe that this is an excluded decision that the Court is not entitled to make.

The relationship between legislation and guidance is set out clearly in our constitution: “the executive (government) cannot change law made by Act of Parliament, nor the Common Law”, as recently confirmed by the Supreme Court in Rule 1 of R Miller v DExEU (2017).[19] This is due to Article.1 of our 1688 Bill of Rights, which states “That the pretended Power of Suspending of Laws or the Execution of Laws by Regall Authority without Consent of Parliament is illegal”. It is therefore unlawful for government guidance to provide an interpretation that cannot be reasonably established by reading the actual words of a statute. This is why government guidance should be considered hearsay evidence when considering statutory interpretation.

There is no statute that defines what parental responsibilities entails. It is however set out clearly in Gillick’s case[20] that parental rights for a child flow from parental responsibilities, which diminish as a child develops competency and so a person’s parental responsibilities will vary from case to case. There are therefore no such things as abstract parental rights. Parents do however have a right at Common Law to exercise their parental responsibilities and to expect that they will not suffer unreasonable interference when discharging them.

It is accepted at Common Law that parents are entitled to exercise parental responsibility, including an entitlement to make decisions on behalf of their children who are under the age of 18, if they lack capacity. Our view is that unless an express statutory provision prohibits the exercise of parental responsibility on behalf of an adult child who lacks capacity, then the parent remains entitled to exercise it and to make decisions on their behalf.

The Act itself confirms that parents of an adult who lacks capacity retain responsibility, which can only be parental responsibility in this context. This is because s.44 of the Act[21] causes the parent of an under or over 18-year-old to be liable for summary or indictable criminal prosecution if they ill-treat or wilfully neglect them whilst they care for them.

The Court should not reasonably fear being excluded from interfering with the discharge of parental responsibility for an individual over 18 who lacks capacity, because that is after all no different to the status quo for arguably more vulnerable children who lack capacity who happen to be under the age of 18. Neither does it render the Court powerless; they continue to have power under s.15 of the Act[22] to declare that a parent lacks capacity to exercise their parental responsibility, noting that s.1(4) of the Act[23] states that “A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because he makes an unwise decision.”. They can also assume authority by convicting a parent under the offences discussed above.

If this provides sufficient safeguarding for a child under 18 who lacks capacity then it must be sufficient for an adult who is over the age of 18. It also goes without saying that a parent who has taken responsibility for a child from before birth to the age of 18 is highly likely to be competent to continue to care for them into adulthood, if they choose to do so. Such a person is also likely to have more care experience than many professionals in the care sector, with a pair of parents having between them a minimum of 36yrs experience once their child reaches 18. They will likely know their adult children and care for their best interests better than anybody else ever could with unreasonable interference inevitably causing a general breakdown of trust within the care process that can only be detrimental to the adult’s best interests.

This parental rights issue could be tested in court or the guidance could be formally challenged. If the Court fails us, there could be a campaign to have the law and guidance amended and clarified to safeguard the right to exercise parental responsibility and to protect the sanctity of the family unit. There could also be a campaign to amend s.27 to expressly exclude the Court from interfering with decisions by approved deputies and those with lasting power of attorney and decision made by certain next of kin relationships, such as spouses, where lasting power of attorney is not in place. There should be no reason to object to this given that the Court is responsible for overseeing these appointments. If the person is capable of being appointed, then they ought to be provided a right to exercise judgement.

It is astonishing that such misinterpretations of the law can influence court decisions for years if not decades and go unchallenged. The consequences include untold stress and suffering for the individuals and their families.

It is high time to challenge the status quo and bring this practice to an end.

- [1] SS v Richmond [2021] EWCOP 31 https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCOP/2021/31.html

- [2] Case of Proclamations (1610) : [1610] EWHC KB J22 https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/KB/1610/J22.html

- [3] s.III “Form of Oath and Administration thereof” Coronation Oath Act (1688) https://www.legislation.gov.uk/aep/WillandMar/1/6/section/III

- [4] In 1855, the US Supreme Court ruled that the words “Due process of law” found in the US Constitution’s 5th & 14th Amendments were intended to have the same meaning as “By the law of the land” in Magna Carta, see Murray v. Hoboken Land, 59 U.S. 272 https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/59/272/

- [5] Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 11

https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/docs/uksc-2013-0136-judgment.pdf - [6] Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 1 WLR 583 www.swarb.co.uk/bolam-v-friern-hospital-management-committee-qbd-1957

- [7] Rogers v Whitaker [1992] HCA 58; (1992) 175 CLR 479(19 November 1992) http://www.paci.com.au/downloads_public/court/12_Rogers_v_Whitaker.pdf

- [8] Mental Capacity Act (2005) s.185 “Interested Persons” https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/schedule/A1/part/13/crossheading/interested-persons

- [9] s.30-34 “Research” Mental Capacity Act (2005) https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/part/1/crossheading/research

- [10] COVID-19 Post-implementation vaccine surveillance strategy https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccine-surveillance-strategy

- [11] The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004, Part 2 of Schedule 1 “Conditions and principles which apply to all clinical trials” www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2004/1031/schedule/1/part/4/made

- [12] World Medical Association “Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects” www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- [13] The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004, Part 5 of Schedule 1 “Conditions and principles which apply in relation to an incapacitated adult” https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2004/1031/schedule/1/part/5/made

- [14] S.27 Mental Capacity Act (2005) “Excluded decisions; Family relationships etc.” https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents

- [15]1 Department for Constitutional Affairs (2007) “The Mental Capacity Act 2005 Code of Practice, Third Impression” Department for Constitutional Affairs

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mental-capacity-act-code-of-practice

- [16] s.50 Mental Health Act (2005) “Applications to the Court of Protection” https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/section/50

- [17] Children Act 1989 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1989/41/section/3

- [18] s.64 Mental Health Act (2005) “General Interpretation” https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/section/64

- [19] R Miller v DExEU [2017] UKSC 5

- https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/docs/uksc-2016-0196-judgment.pdf

- [20] Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Health Authority [1986] AC 112 https://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/1985/7.html

- [21] s.44 Mental Health Act (2005) Ill-treatment or neglect www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/section/44

- [22] s.15 “Power to make declarations” Mental Capacity Act (2005) https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/section/15

- [23] s.1 Mental Capacity Act (2005) https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/part/1/crossheading/the-principles