Another nail in the mandate coffin

Mandating vaccinations is morally wrong because it breaches bodily autonomy — a fundamental human right and the foundation of ethical medical practice.

The argument for mandating vaccination in healthcare workers is that it will protect their patients. The suggestion that unvaccinated healthcare workers do not care about their patients is offensive and the claim that vaccines can protect patients does not stand up to the slightest scrutiny.

Somehow the debate ignores that key point, and instead focuses on whether these novel vaccines could reduce infections if everyone were vaccinated. There are two key issues when addressing that question

- Does being vaccinated reduce the risk of being infected?

- If infected, does being vaccinated reduce the risk of transmission?

First, let’s address the heart of the issue. Politicians are right to be concerned about nosocomial (within hospital) transmission as a key driver of infections in the most vulnerable. Indeed, SARS-1 and MERS, where testing was limited to severe cases, were also primarily spread in hospitals. So who is doing the spreading? Cambridge University carried out a careful study of the genetics of the virus in hospital to understand the source of infection in their patients. This is not an exact science as the source can never be proved, e.g. a third party could have been the source for more than one person but a delay in testing positive for one person would make it appear that they acquired the infection from the person who tested positive first. Nevertheless, their work showed that sick patients were the ones spreading it to other patients, not the staff.

Given what we know about viral production this is not surprising. Infected individuals emit 1,000 to 100,000 virus particles a minute and that figure is likely to be higher in those with a poor immune response. The measure of viral production at different stages of the illness is always distorted by being presented on a logarithmic scale. The real spike in viral production is very short lived at the outset of the illness. This realisation has led to calls for a shortening of the isolation period but the same logic has not been applied to conclude that the viral production in the presymptomatic period is negligible. Once respiratory tract cells are turned into virus producing factories, cells are damaged and consequently symptoms develop.

Viral particles filled the air in hospitals in winter in much the same way that indoor environments all contained an infectious dose of influenza in winter in previous years. This represents a challenge in terms of adequate hospital ventilation and separation of the sick. However, vaccinating or sacking healthcare workers will not change this dynamic one iota. That would be true even if vaccines could reduce infections, because the hospitals will still be full of sick people producing far more virus than any presymptomatic health care workers.

Does being vaccinated reduce the risk of being infected?

The vaccines were sold on the basis that vaccines had a dramatic effect on reducing symptomatic infections, but even at the time researchers had many questions about how this and other vaccines will perform as they were rolled out to millions of people. Real world evidence shows that they have not achieved what they set out to do. One plausible explanation is that the evidence used to support the case is based on vaccines resulting in infections in the susceptible being brought forward to the two weeks after vaccination. Only measuring the period afterwards leads to the illusion of success because the vaccinated at that point are either not susceptible to that variant, immune to it having just been infected… or dead.

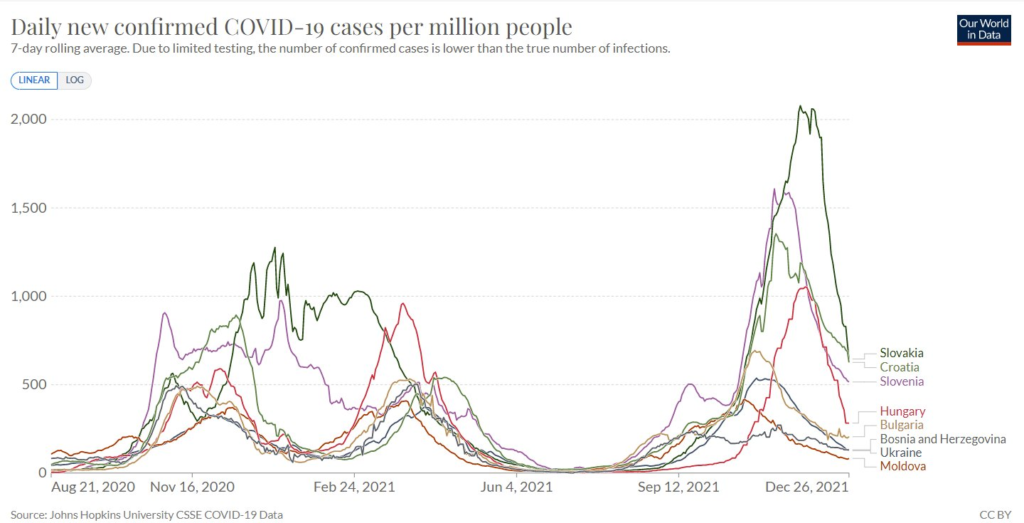

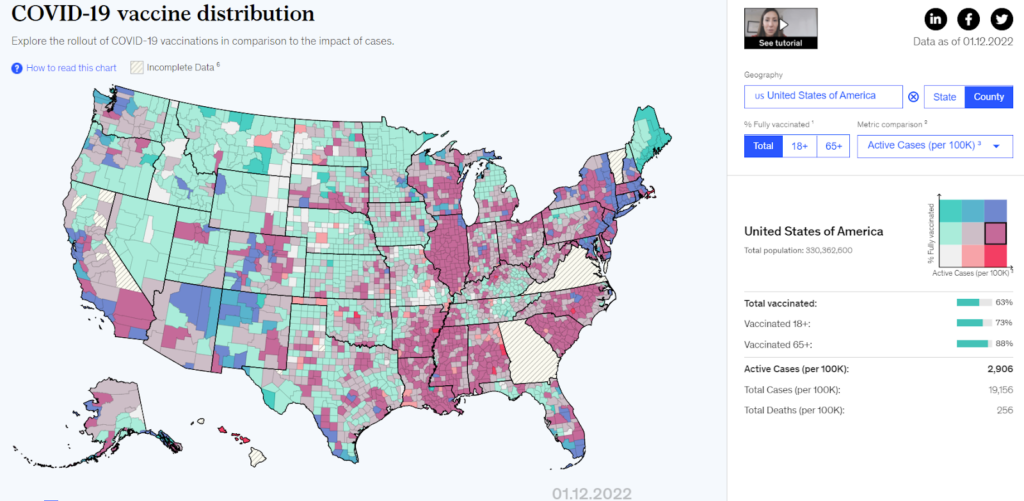

Comparing countries or regions within countries shows that those with the highest vaccination rates have had the highest case rates of late. This was true in Eastern Europe in Autumn (see figure 1), in the United States (figure 2), Germany and England more recently. Covid-labelled deaths in Eastern Europe by country were similar regardless of vaccination rates.

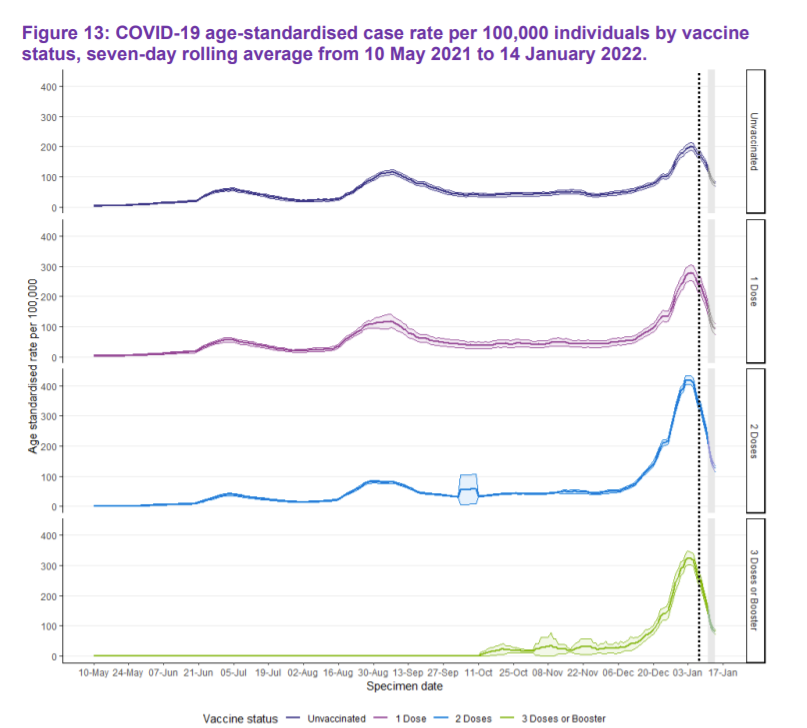

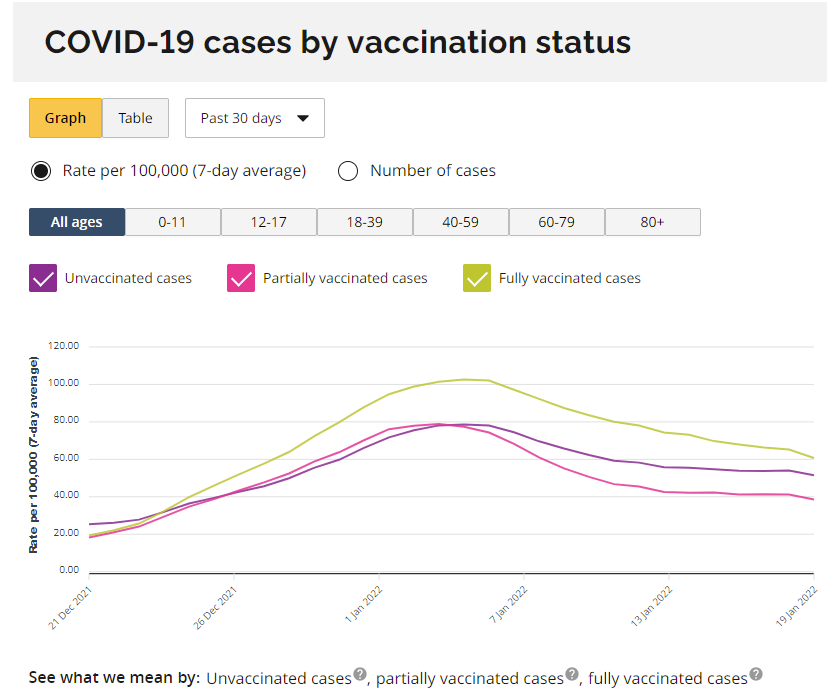

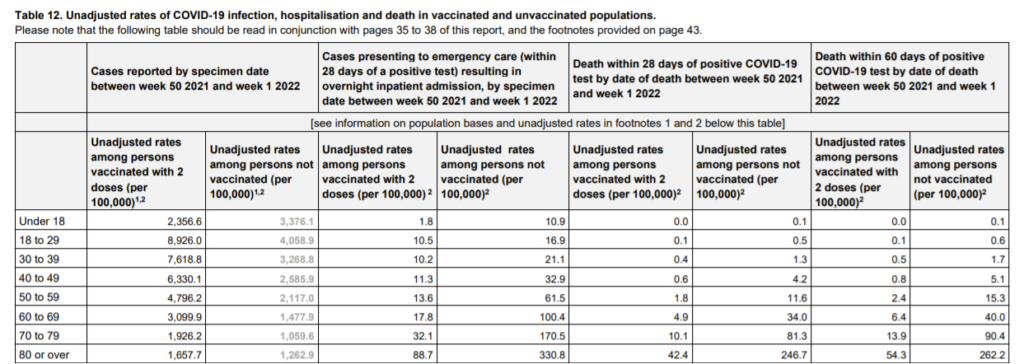

Those countries that report on case rates by vaccination status show a higher rate in the vaccinated than the unvaccinated. To emphasise, these are not absolute numbers of positive test results but the number of positives per 100,000 of that particular population. The rate is also higher in the double-dosed than the single-dosed, and the sizes of these particular populations should be very accurate as both have been actively recorded in the vaccine database. This is evident in:

Scotland, where the rates peaked at a similar level in September by vaccination status (100 on the y-axis) but are now twice as high in the unvaccinated, three times as high in the single dosed and triple dosed and four times as high in the double dosed:

Ontario, where rates in the fully vaccinated have been higher than both the unvaccinated and partially vaccinated since December:

England, where case rates have been so much higher in the double dosed that UKHSA wanted the unvaccinated rates to fade into oblivion so they reported the data in light grey:

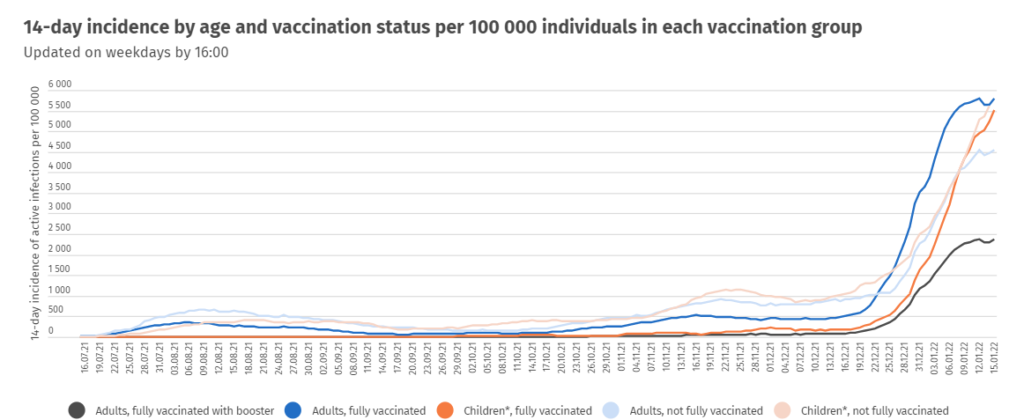

And Iceland, which is a small enough country to allow very accurate estimates of the whole population size and where rates in vaccinated adults are substantially higher than in the unvaccinated:

It is possible that the discrepancy arises to some extent because the unvaccinated have had more prior infections, hence their decision not to be vaccinated, making them a more immune population, but not at all diminishing the significance in terms of policy — of the data. It is somewhat surprising that, despite extensive research into Covid, no country has done the simple investigations required to answer the question of the level of naturally acquired immunity in the vaccinated and unvaccinated populations.

If infected, does being vaccinated reduce the risk of transmission?

Transmission is very hard to measure, not least because of the problem of the variable incubation period making it hard to be certain of the source. As a surrogate, it is possible to try and quantify the amount of virus present in the airway, on the basis that this should represent how much virus is being emitted. Experiments measuring the levels emitted by vaccinated and unvaccinated people show that the levels of virus present are the same. In fact a third of vaccinated patients had very high viral loads. The duration of illness is also the same regardless of vaccination status. If vaccine does achieve symptom reduction, then in the absence of a reduction in viral load, the overall risk of community transmission could increase as people would be unaware that they were infectious.

No logical reason to think these vaccines would reduce infections

Injected vaccines act only on the blood. They stimulate blood-borne antibodies which may play a role once an infection is established. However, the parts of the immune system that prevent a virus entering a cell in the respiratory tract are not stimulated. These parts of our immune systems are multifaceted but include a different type of antibody that is secreted onto the surface of the respiratory tract. Being able to prevent virus from entering a cell and establishing an infection is a worthy goal and that is why considerable time and money has been spent on trying to develop nasal vaccines which would achieve this.