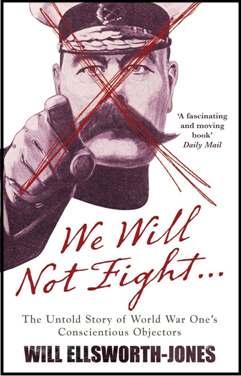

The Untold Story of World War One’s Conscientious Objectors

“There was a big concourse of men lined up in an immense square. Under escort we were taken out, one by one, to the middle of the square. [Howard Marten] was the first of them… Then the officer in charge… read out the various crimes – refusing to obey a lawful command… and so on. Then: ‘The sentence of the court is to suffer by being shot’.There was a suitable pause, and [Marten] thought, ‘Well, that’s that’. Then he said, ‘Confirmed by the Commander in Chief,’ Field Marshall Haig, which double-sealed it. There was another long pause – ‘But subsequently commuted to penal servitude for ten years’. And that was that…”.

Like with so much history that is shrouded by the mists of time, the detailed tales of the thousands of British men who refused to fight in the First World War make for fascinating reading. These conscientious objectors came from all walks of life – socialists, communists, pacifists, Quakers, Jehovah’s witnesses, Methodists, the Bloomsbury Set – and found a unity of purpose in their protest, allowing them – for a time being at least – to put aside quite substantial ideological differences.

And while history does not repeat itself exactly, it certainly does seem to rhyme.

“In all revolutions the vanquished are the ones who are guilty of treason, even by the historians, for history is written by the victors and framed according to the prejudices and bias existing on their side“

Missouri Senator George Graham Vest, 1891

Published in 2008, Will Ellsworth-Jones has pulled together the various strands of the story into a moving compilation, following the four Brocklesby brothers as they miraculously survive the hazardous years of World War One. They are the lucky ones. The quirk is that one of them – the eldest, Bert – is a conscientious objector who not only refuses to fight (many of those unwilling to bear arms choosing instead to serve in ambulance and non-combatant corps), but is unwilling – in any way – to contribute to the war effort. He therefore refuses, for example, to peel potatoes for troops or perform any sort of menial task that might support anyone or anything involved in the war effort. This reluctance to answer a call to arms became illegal after the – controversial and ‘un-British’ – introduction of conscription by the Military Service Act in January 1916. This was a first. Conscription bills had hitherto always been defeated in Parliament.

Bert was one of 35 holdout conscientious objectors who – after arrest, a period of incarceration and then general mistreatment by the army – were shipped over to France, despite it being abundantly clear by this point that they would in no way contribute to the army’s expeditionary activities. Thus there could be – and in fact was – only one reason for doing so, namely to fabricate a situation whereby the army could court-martial these ‘conchies’, as they were condescendingly referred to, for disobedience. Only in a theatre of war would this result in the death penalty. Desperate for recruits during the middle stages of the War, various senior army leaders were keen on setting such a grotesque precedent, which (they hoped) might act as an (albeit unethical) deterrent to persuade peaceniks back home from following in the conchies’ footsteps. It was only the actions of quiet – yet determined – campaigners, who worked to get the ear of Prime Minister Asquith, who were able to stay the hand of an army leadership that had strayed into the most immoral of territories in deliberately seeking to engineer the demise of those that objected to the use of force.

What is extraordinary about the whole sorry tragedy of the First World War is the utterly depraved levels of violence and the totally unnecessary nature of the wanton killing, seemingly limited only by the rapidity with which men could be transported to the various fronts to be inefficiently mown down. There was no existential threat to the Western World – unlike in WWII. There was no pathologically evil enemy to contend with. The various fronts remained essentially static for much of WWI – what was the bloodshed actually for? The death, pain and loss inflicted on both sides contributed to the harshness of the Treaty of Versailles, which fuelled resentment in Germany, perhaps providing fertile ideological ground that led to the creation of the Third Reich and an escalation of mechanised killing. While we commemorate Armistice Day every year (“Lest We Forget”), it does seem that the underlying banal stupidity of WWI remains somewhat embarrassingly hidden from view. We would do well to remember this, as well as the circumstances around which such a conflagration was allowed to escalate from playground politics to deadly warfare:

“Two days before war broke out the Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson, had preached a prescient sermon in Westminster Abbey: ‘What is happening is fearful beyond all words… the thing which is now astir in Europe is not the work of God but the work of the Devil’. But by the time of his Christmas pastoral letter the Devil was loose and now the question was not stopping the war but winning it: ‘I think I can say deliberately that no household or home will be acting worthily if, in timidity or self-love, it keeps back any of those who can loyally bear a man’s part in the great enterprise on the part of the land we love’”.

That is certainly a message of sacrifice. Looking back, it somewhat boggles the mind that an omnipotent God could have had a change of heart over the space of four short months. One can therefore only conclude that even men of the cloth such as the Archbishop had succumbed to the hysteria of the day. And we know that – once in train, not unlike the timetabling that took on a life of its own via the Schlieffen Plan that swept German troops through Belgium in August 1914 – such collective hysterias are usually very difficult to derail, both in terms of time and otherwise needlessly incurred hardship, pain and suffering.

The tempering voices of wise old heads may have helped quell the war-lust at the point of ignition, but once the flames had been fanned into an inferno, this became a much graver task, no pun intended:

“In 1914, as Churchill later wrote, ‘men were everywhere eager to dare’. Julian Grenfell, who attended Eton and Oxford before joining the Royal Dragoons, wrote to his mother, a fashionable London hostess, in the understated style of his class: ‘It is all the most wonderful fun, better fun than one could imagine. I hope it goes on a nice long time. I adore war, it is like a big picnic without the objectlessness of a picnic’. Instead of partridges he listed in his Game Book dead Germans. ‘One loves one’s fellow man so much more when one is bent on killing him’. After being decorated for bravery he was himself killed in May 1915”.

And so matters played themselves out. War became the ‘current thing’ of the day that could not be questioned such that only attrition – on an industrial scale – could slowly bleed the joy of war out of the enthusiasts that were lucky enough to escape Grenfell’s fate:

“… in September [1915] came Loos where 16,000 men lost their lives and 25,000 were wounded. The Germans were so horrified at the massacre of line after line of men that they held their fire as the British retreated… never before had machine guns more straightforward work to do, nor done it so effectively”.

Did this unspeakable slaughter in any way stay the hand of the military planners? Of course not. Rather than staunch the flow of blood, a predominant theme was to pour out more: “Send More Men” was a recurrent propaganda theme, one that continued into the concluding chapter of the war, a senior American general stating that his newly arrived troops were “here to be killed… how do you want to use us?”.

And so the horrors continued to the denouement – final artillery shells being timed to perfection such that a deathly hush ensued at precisely 11am on 11 November 1918. Even in those last hours, minutes and seconds of the war – when the futility of ongoing fighting was obvious to all – the bloodlust needed to be slated.

Did the conchies fail? Great minds have pointed out that Against Stupidity the Gods Themselves Contend in Vain, and a few hundred (or even thousand) ‘conchies’ were unlikely to avert the great misadventures of an indulged society hell-bent on destruction. Yet at great personal cost, despite not suffering the ultimate punishment as envisaged by their court-martials, surviving conscientious objectors found it hard to find gainful employment after the war. They nonetheless succeeded in securing the principle of conscientious objection in Britain, which is more than can be said about many other countries.

To deliberately misuse a military term, Bert Brockelsby, Howard Marten and their fellow objectors led from the front – in an intellectual and moral sense – reminding later generations to think ever so carefully about just ‘going along’ with the ‘current thing’ and what politicians and large bureaucratic organisations (industrial-military-medical complexes included) might tell us is in our best interests.

Have these lessons been learned? Possibly. One would like to think that events that took place over a hundred years ago might weigh on the minds of those living in the present.

Lest We Forget, therefore, let it be written here in April 2024: we owe the WWI conchies a huge vote of thanks for further establishing the principles of conscientious objection and pushing back against mandatory conscription and other such evils.

Why do we say “further establishing”? Ellsworth-Jones’ story requires an addendum, not covered in his book. The term ‘conscientious objector’ was, in fact, already an established term which was used to describe those who objected to ‘scarification’, an early — and very crude — form of vaccination, where an unknown concoction from a victorian glass vial would be introduced into the body in the hope that it would prevent smallpox. The 1898 Vaccine Act introduced a ‘conscientious objector’ clause which allowed people to make a conscious decision to decline the intervention for themselves or their children. With the majority of exemptions being sought by the working class, some of those in authority — in an attempt to impede the use of this lawful exemption — argued that these claims were from people without a conscience, and therefore they couldn’t be conscientious (and so the clause couldn’t apply).

Mirroring more recent discussions about informed consent, it would seem this is another example of history that rhymes, albeit with a somewhat discordant melody.

Conscientious objection: a timeline of events amidst the unfolding of a collective delusion/deception:

- Society is led to fear a great enemy – an ‘emergency’ is duly declared or fabricated;

- Rational objections are dismissed and a censorship regime is enforced (or enhanced if already in place);

- Emotions are manipulated to exaggerate threat, normalise unethical behaviours and set actions in motion that lead to more harm;

- The Archbishop of Canterbury (and other high profile religious leaders) are deployed to shepherd their flocks into the holding pen of conformity;

- The ensuring (self-)inflicted harm leads to a ‘doubling down’ of the introduced courses of action to ensure that said actions were not in ‘vain’ (of course, admitting error early in the piece necessitates admitting fault and a guaranteed downfall… it is entirely rational for weak leaders, crooks and scoundrels to seek to avoid such an ignominious fate by perpetuating the ‘emergency’ that has brought them to power);

- Rather than recognise that conscientious objectors might have had a point all along, they are deemed a threat and needlessly & cruelly persecuted, serving a dual purpose of uniting the majority against the minority and thus bedding in the official narrative;

- Inevitably, the harmful course of action is compounded by statistical fudges and McNamaran fallacies whereby proxy measurements of success (e.g. “send more men”) only compound the failures;

- To avoid future culpability, large bureaucracies and entities that are responsible (or have benefitted) from the implementation of the harmful actions go to enormous lengths to obfuscate, cover up and hide the detail surrounding key decisions made around the establishment of the ‘emergency’;

- Key narratives are repeated via propaganda channels to assuage the questions of the masses that inevitably arise so as to uphold the official storyline.

- Veils are drawn, such that painful matters of the past are conveniently

forgotten‘consigned to history’, along with an admission that ‘mistakes were made’; - In certain cases, earnest hand-wringing accompanies requests for amnesty along with requests to ‘move on’ to the latest current thing.

It is a matter of great comfort and reassurance that – having learned these lessons from history – we live in enlightened times where thankfully such misadventures are surely a thing of the past!